Feature

Sea change: naval uncrewed operations

As combat use cases for USVs are demonstrated in the Ukraine‑Russia war, the take‑up by services around the world of uncrewed maritime systems continues to grow. Gordon Arthur reports.

The Ghost Shark is being jointly developed by Australia and Anduril. The first prototype was unveiled in Sydney in April 2024. Credit: Anduril Australia

While uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAV) have become de rigueur for militaries around the world, uncrewed maritime vessels are also growing in popularity and utility, with the range of expected missions they are able to perform similarly expanding.

Uncrewed surface vessels (USV) have dramatically hit headlines thanks to their use by Ukraine against Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. In February, multiple Magura V5 craft – a 5.5m-long USV that displaces less than one tonne, has an 800km range and 78km/h top speed – sank the Russian corvette Ivanovets.

Importantly, Russia’s Black Sea Fleet is now essentially confined to port, due in significant part to Ukraine’s USV flotillas.

Indeed, the Ukraine war may well represent a new era in naval-drone warfare, demonstrating true asymmetric effects. Despite an estimated kill-to-loss ratio of 1:10, Ukraine’s USV swarms eliminate risk to life because no crew are aboard. Furthermore, their diminutive size, minimal infrastructure requirements, speed and one-way strike range are all advantageous.

USVs do have vulnerabilities, but their Black Sea usage is demonstrating to even powerful navies that they do pose a serious threat. Of course, smaller nations or insurgent groups can wield these low-cost, attritable tools, as Yemen’s Houthis are against commercial shipping in the Red Sea.

USVs: market forecasts

Analytics firm GlobalData predicts the current worldwide USV market will more than double to $2.5bn by 2034, up from $1.1bn this year. It forecasts a market compound annual growth rate of 6.7% from 2025-29.

It stated: “The proliferation of unmanned systems in the global defence market continues to have a growing impact on the future of naval warfare, following Ukraine’s successful campaign against the Russian Black Sea Fleet.”

GlobalData lists China, France, Russia, South Korea, Turkey, and the US, as major USV players.

Fox Walker, a GlobalData analyst, predicted: “Such drones will become increasingly important for countries focused on the Indo-Pacific region. The development of larger, more versatile USV platforms has become both an economic and strategic imperative for the US Navy (USN) as it continues its strategic competition with Russia and China.”

The proliferation of unmanned systems in the global defence market continues to have a growing impact on the future of naval warfare

GlobalData

The US has multiple USV programmes, and the US Navy (USN) recently launched Project 33 to rapidly integrate robotic systems by 2027. Additionally, Task Force 59 is testing diverse platforms like Saildrone’s Explorer and MARTAC’s Mantas T38.

USVs are important to the USN’s distributed maritime operations concept, and the first Large Unmanned Surface Vehicle (LUSV) is to be procured in FY2027, two in FY2028 and three in FY2029. The proposed 1,000-2,000-tonne LUSV might carry strike payloads with 16-32 missile cells.

As for the Medium Unmanned Surface Vehicle (MUSV), the USN issued a request for information in June 2024 for the first to be delivered within a year, and up to six more within two years. The service wants a proven design displacing less than 500 tons.

Furthermore, a Littoral Combat Ship will deploy with a mine countermeasures (MCM) mission package for the first time in FY2025, which includes a USV and Knifefish underwater vehicle. The MCM package’s wider utilisation will allow the USN to divest MH-53E helicopters and Avenger-class MCM vessels.

Considerable work is also occurring in Australia. Shipbuilder Austal converted a decommissioned Armidale-class patrol boat into a proof-of-concept uncrewed platform, successfully testing it for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). Austal has now strategically teamed up with Greenroom Robotics to develop technologies to “reduce crewing, increase safety and enable remote and autonomous operation of vessels”.

With an eye on future Australian, British, and American requirements, their agreement aligns with one of AUKUS Pillar 2’s objective to develop autonomous military capabilities.

The RAN also turned to Ocius Technologies for its 6.8m-long Bluebottle persistent intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) USV that leverages solar, wind and wave energy. The RAN has ordered 14 Bluebottles, which are helping monitor Australia’s maritime approaches, including through the utilisation of Thales’ thin-line towed arrays.

The Bluebottle has brought Ocius Technologies sales in Australia, New Zealand, and the USA. Credit: Gordon Arthur

Such unmanned vessels can perform 24/7, persistent and monotonous tasks, freeing up crewed assets to peform other maritime roles.

Another country to watch is China, with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) known to be utilising USVs. Indeed, Chinese companies are also marketing USVs on online shopping platforms such as Alibaba, some of which are suitable for conversion into attack vessels.

Elsewhere in the Indo-Pacific region, Singapore was an early adopter of USVs, with the Republic of Singapore Navy utilising ST Engineering’s Venus 16 in the MCM role: one platform carries a Thales towed array to detect mines, while its partner has an expendable neutralisation system.

Furthermore, the Singaporean Navy has also been using four 16.9m-long maritime security USVs since 2021.

UUVs: operationally commonplace

Uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUV) have long been used for hydrographic surveys, MCM, rapid environmental assessment, ISR, infrastructure inspection, intelligence preparation and salvage. Now seafloors are becoming a new and more public arena for warfare, as evinced by Russia’s tampering with undersea cables.

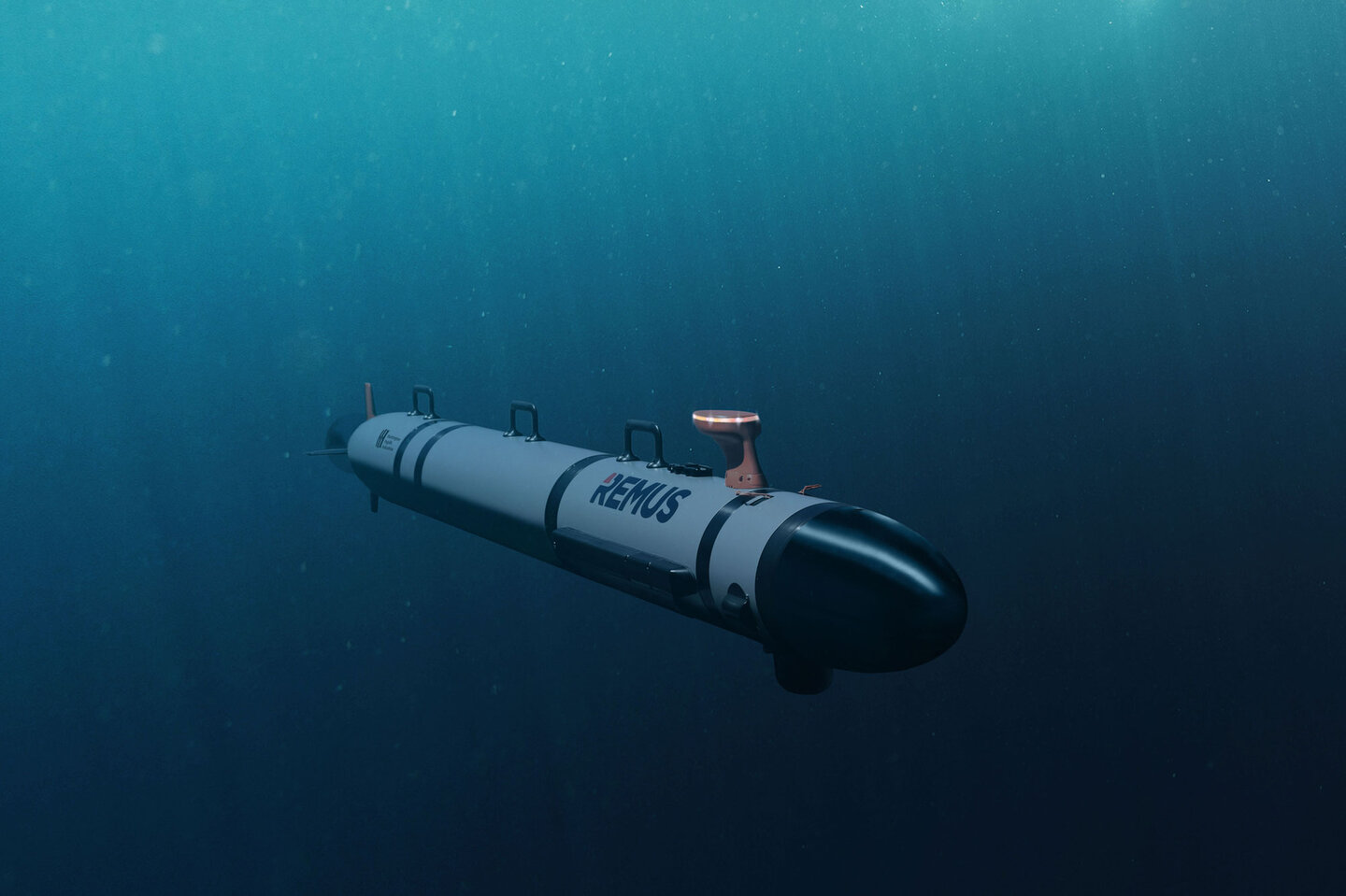

The USN makes a useful study of how navies employ UUVs. Its family of systems is extensive, with the FY2025 budget allocating $191.5m. Last year, HII, the world’s largest UUV producer, was awarded a contract for nine initial Lionfish small UUVs, and potentially up to 200 over the coming five years. The portable Lionfish is based on the REMUS 300.

Moving up in size, the medium MUUV category includes General Dynamics Mission Systems’ Bluefin-21-based Knifefish, plus the REMUS 600-based Razorback for submarine use. Previously, submarines could only launch Razorbacks from a dry shelter and recover them by surfacing.

However, a new torpedo tube launch-and-recovery system will revolutionise operations. The Virginia-class nuclear powered submarine USS Delaware will deploy with the new system and a Razorback for the first time in 2024 for tests. Certainly, one priority for AUKUS Pillar II is the ability to launch/recover UUVs from submarine torpedo tubes.

Also in the MUUV category, the USN awarded a contract to Leidos in 2022 to develop the next-generation MCM MUUV known as Viperfish, based on L3Harris’ Iver4 900 UUV.

Its purpose is to go into harm’s way, to places and at times when there’s low appetite to risk human life

David Goodrich, CEO of Anduril Asia-Pacific

At the large end of the UUV scale, the USN decided earlier in 2024 to restart its Snakehead LDUUV programme, selecting in February Oceaneering International, Kongsberg Discovery and Anduril Industries to deliver prototype LDUUVs.

The USN is also exploring the use of extra-large UUVs (XLUUV) via Boeing’s 15.5m-long Orca; the first was delivered in late 2023, and it will inform development of five further prototypes in due course. The Orca could eventually perform mine warfare, ISR, anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare, electronic warfare, MCM and strike missions.

XLUUVs are actually booming, with diverse countries working on various projects, with one example in Australia, where the RAN’s submarine fleet languishes because of programme delays, providing the opportunity for XLUUVs to help fill capability gaps. Following a 2022 contract, Anduril Australia delivered its first Ghost Shark XLUUV prototype to the RAN in April 2024 a year ahead of schedule. Anduril will deliver two more by June 2025.

On 5 August, Australia and Anduril Australia concluded a co-funding contract that requires each party to invest $13.3m to accelerate the programme “from prototype development to production”. A manufacturing facility will be built there, serving both domestic and export customers.

Canberra said the Ghost Shark offers a “cost-effective, persistent ISR and strike undersea capability,” and Anduril Australia added, “Ghost Shark will provide stealth, disruptive mass and persistence, optimised for the Indo-Pacific archipelagic environment.”

It is unknown how many Ghost Sharks Australia will procure, or how they might interoperate with other RAN platforms. However, Anduril Australia told Global Defence Technology: “Its purpose is to go into harm’s way, to places and at times when there’s low appetite to risk human life, but where it’ll provide an asymmetric challenge to adversaries that will be difficult to address.”

HII’s REMUS 300 UUV has a depth rating of 305m. Credit: HII

Anduril has also recently delivered one company-funded XLUUV to the US too, with David Goodrich, CEO of Anduril Asia-Pacific, stating: “The way you build competence, confidence and trust in autonomy is to get many, many repetitions into your test and evaluation plan to test your algorithms and to build the CONOPS.

“Having two independent but related teams of engineers working on either side of the Pacific helps us double or triple the speed at which we can test those algorithms.”

Technology companies like Anduril are rewriting the rulebook by rapidly developing unmanned systems like Ghost Shark. Goodrich explained Anduril benefits from its Silicon Valley DNA and philosophy of “software first, hardware second” and “show me, don’t tell me” methodologies.

“We don’t do a full design and full build and then do testing … We’re testing a little, we’re designing a little, we’re testing a little, we’re demonstrating, we’re learning and we’re hitting that loop again.” Goodrich added.

“We don’t do prototyping, come up with a terrific idea and then think, gee, how are we going to build this? We’re thinking, how are we going to build this in an economically sensible manner using materials, systems, processes and procedures that are well tested?”

Elsewhere, China unveiled two HSU001 LDUUVs in 2019, but there are no indications how the PLA is using them. Chinese-built Haiyi sea gliders – possessing a 60-day endurance – have also turned up in numerous strategic locations as China busily collects data for submariners.

Autonomy a key factor

USVs with kinetic payloads are already being used in combat, so it should be no surprise when navies start arming UUVs with weapons like torpedoes and mines. Increasing trust from users, as well as technological developments, will augur in the full spectrum of undersea warfare.

However, even as uncrewed technologies move up the autonomy scale, probably no military is yet ethically comfortable with allowing armed uncrewed systems to fully make their own decisions.

China’s HSU001 large-displacement UUV debuted in a Beijing parade in 2019. Credit: Gordon Arthur

Also, questions remain or maintenance while on operation. With no sailors aboard, even a simple technical issue can render a craft useless. Sufficient bandwidth in contested environments is also necessary, but uncrewed systems may struggle against properly defended targets. Nonetheless, despite some drawbacks, UUVs and USVs represent affordable force multipliers.

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.