Feature

Layered approach: the future of air defence

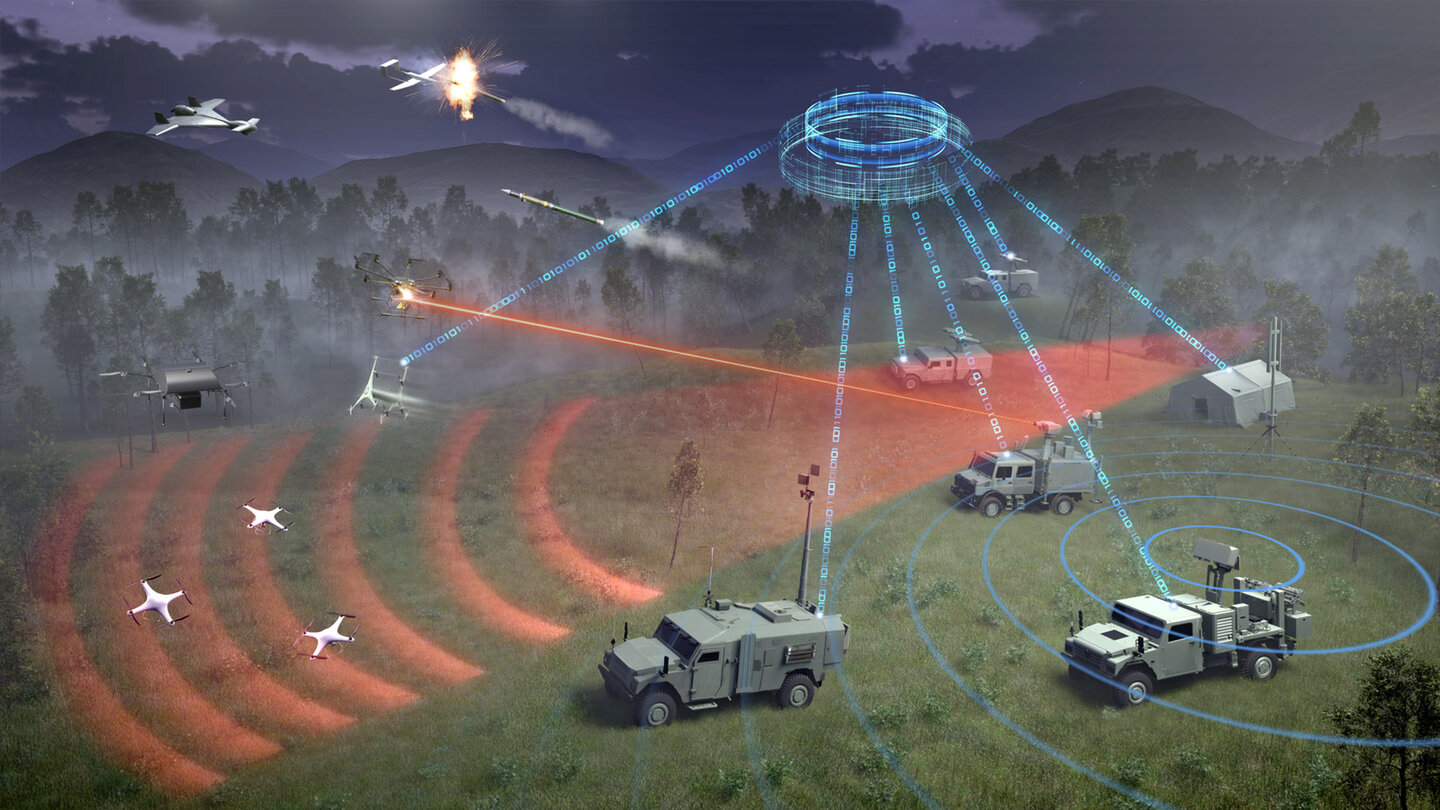

Amid a growing threat picture for land forces, the need to develop complementary air defence networks is critical. Gordon Arthur reports.

The SAMP/T NG system fires MBDA’s Aster family of surface-to-air missiles. Credit: MBDA

Not only must air defence systems – usually gun- or missile-based – defend against traditional air-breathing targets such as aircraft and helicopters, but contemporary conflicts have become much more complicated due to the proliferation of uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAV), loitering munitions, and cruise missiles.

In fact, GlobalData, in its UAV market forecast for 2024-34, predicted the global market will grow at a compound annual growth rate of 6.3% to reach $25.7bn by 2034. The same report stated that while loitering munitions accounted for 10% of the global UAV market in 2024, it will have the highest growth rate of any UAV segment till 2034, at 7.1% over the next decade.

With such an expansion of aerial threats, the calculus for ground-based air defence (GBAD) has become far more challenging.

Layering and integration

US President Donald Trump is jumping feet first into air defence, after passing a vaguely worded executive order mandating “Iron Dome for America”. This intent is seemingly based on Israel’s Iron Dome system, which has a high interception rate against rockets, artillery, mortars, UAVs and air-breathing threats launched from 4-70km away.

Whilst Iron Dome is ideal for countering militants’ rockets fired against the small territory of Israel, it is difficult to see how it could protect the United States from the more likely ballistic and hypersonic missile threats that it faces from adversaries like Russia and China.

GlobalData expects global missiles and missile defence systems to grow at an average annual rate of 5.3% over the coming decade to reach $76bn by 2034. Alarmed by Russian antics in Ukraine, Europe is investing in air defence, with France acquiring SAMP/T NG systems and the Netherlands the Patriot, for instance.

There’s still a need to be able to defend against a wide spectrum of threats – MBDA spokesperson

Leonardo UK spokesperson

European nations are also clubbing together to integrate their air defence networks at a continental level via the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI).

Asked whether there is still a place for expensive surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems, an MBDA spokesperson told Global Defence Technology: “The trends and character of current conflicts around the world portray a complex environment with multiple threats. Conventional and non-conventional weapons and tactics are being used to gain tactical, operational and even strategic advantage.

“Therefore, despite the prevalence of the drone/loitering munition threat, there’s still a need to be able to defend against a wide spectrum of threats, from improvised weaponised quadcopter drones, to uncrewed combat aerial vehicles and loitering munitions, through to cruise and ballistic missiles, as well as the airborne platforms that deliver some of these threats.”

The representative added: “This means there’s still a strong place for air defence, which also covers counter-unmanned aerial systems (C-UAS). To provide it, you need an integrated and layered air defence system of complimentary effectors that provide both military and homeland defence.”

Self-propelled anti-aircraft gun systems are still widely used, such as China’s PGZ07. Credit: Gordon Arthur

MBDA went on to describe the various GBAD layers it has on offer. Its flagship C-UAS system is the Sky Warden, which the spokesperson described as “a scalable system that can effectively neutralise any form of threat, from tactical drones to reconnaissance mini-drones, as well as other traditional ‘air-breathing’ threats”.

Vehicle-mounted or dismounted, it employs artificial intelligence (AI) to assist human operators identify and classify threats, and then automatically assign the most appropriate effector.

Moving up in capability, the Mistral represents MBDA’s very short-range air defence layer. Further on, the European missile house markets the hot-launched VL MICA NG and cold-launched Enhanced Modular Air Defence Solutions (EMADS); the latter utilises the Common Anti-air Modular Missile (CAMM) family.

MBDA notes that the MICA NG is the only missile in the world equipped with two interoperable seekers – an active radio frequency active electronically scanned array seeker for all-weather shoot-up/shoot-down capability, and the second a passive imaging infrared seeker.

The company’s highest-tier air defence product is the SAMP/T NG medium-/long-range system that fires Aster-family missiles. It can operate standalone or integrated into a network and can fire up to eight missiles in ten seconds.

Ukraine’s battlefield experience

It is three years since Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, and the latter’s air defence network is frantically defending military and civilian targets from Russian aircraft and missiles.

As Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said in 2024, “Air defence is the answer.”

Western countries have bolstered Ukrainian air defences with a hodgepodge of disparate systems like the Aspide, Aster-30, Crotale, Gepard, IRIS-T, MIM-23 HAWK, Mistral, NASAMS, Patriot PAC-2, Piorun, RBS 70, Skynex, Starstreak, and Stinger.

MBDA offers the modular Sky Warden system. Credit: MBDA

Interestingly, German-supplied Gepard self-propelled antiaircraft gun systems, first developed in the 1970s, have proven very practical against UAVs thanks to their effective cost-to-kill ratio.

In Ukraine, air warfare has been transformed by the proliferation of precision air attack weapons. Yet these still rely on reconnaissance assets to provide target coordinates, often low-cost UAVs whose cheapness and dense saturation constitute a devilish threat. Such UAVs create high volumes of simultaneous targets and raise the spectre of long-term cost – it is not feasible to use expensive missiles against throwaway UAVs.

Consequently, massed air defence assets of sufficient quality to counter a broad range of threats are required. Yet air defence platforms near, and far, behind the frontlines are under intensive threat from reconnaissance assets, and they can be quickly targeted.

Air defence is the answer

Volodymyr Zelenskyy

Survivability and recoverability are therefore vital considerations for air defence units too. Because radars emit signatures and can be swiftly counterattacked, passive infrared search and track is proving practical for military operators, even if only for short-range targeting.

Ukraine has also developed its Zvook network of passive acoustic sensors, comprising parabolic antennas connected to computer algorithms, to detect air targets.

Furthermore, Ukraine’s experience has shown that anti-aircraft weapons need to be integrated into effective air defence networks. This requires robust communications and command and control. Effectors need to be resupplied with ammunition in a timely fashion, emphasising the need for efficient logistics.

When asked about lessons being learned from Ukraine, a spokesperson from the Australian company Electro Optic Systems (EOS) highlighted three things. The first is that a variety of effectors must be multi-layered. Next, “longer-range effectors are required (part of the multi-layered approach). Rockets and missiles are in demand, but ideally, they must be cost-effective and used against appropriate UAV targets.”

Finally, the EOS representative said: “It’s becoming more difficult for ‘soft kill’ solutions such as jammers and spoofers to remain effective as drones become more hardened against these effects. More and more, it’s the kinetic effectors that have the most effect.”

Defending against drones

Indeed, integration of C-UAS is one of the most pressing issues for GBAD systems. Different technologies are pertinent, and EOS, for example, offers three types of platforms: the Slinger remote-controlled weapon station (RWS) optimised for C-UAS through radar, software and effectors; a laser dazzler; and a high-energy laser weapon.

Asked about what advantages the Slinger RWS brings to the C-UAS role, EOS stated it offers value-for-money engagement of UAVs, and they are platform-agnostic for land or maritime environments.

Additionally, their size and weight allow them to be installed on anything from pickup trucks to main battle tanks. They are versatile too, since they can perform ground-to-ground attack roles when not defending against UAVs.

Meanwhile, Australia is finally moving to eliminate a glaring C-UAS capability gap as it seeks solutions to protect infrastructure, bases, dismounted personnel, and vehicles. Project Land 156 will address the threat posed by UAVs weighing up to 55kg. An approach to market for a systems integration partner to manage C-UAS acquisitions occurred last November, though a minimum viable capability is not expected until 2032.

EOS told Global Defence Technology: “We’ve been working for some time in anticipation of the approval of the Land 156 project. We’re excited that the project is moving ahead and look forward to participating and contributing to the capability.”

EOS markets the Slinger weapon station optimised for counter-UAS missions. Credit: EOS

Illustrating the need to broaden the scope of GBAD, Kongsberg and Raytheon are looking to expand the popular NASAMS system’s capability. John Fry, managing director of Kongsberg Defence Australia, told Global Defence Technology that the partners will bring in full-spectrum air defence with a longer-range missile as well as more tightly coupled C-UAS effectors.

The former would require a new launcher to accommodate larger missiles capable of perhaps even countering tactical ballistic missiles; of course, this is a more cost-effective approach than having to buy a separate system.

Fry noted that, whilst missiles are not suited to shooting down small UAVs, their networked radars are ideal for cueing data to other effectors. Fry said Kongsberg is looking at integrating a C-UAS capability into its fire distribution centre (FDC) and using it as a decision tool for other gun-type air defence systems.

NASAMS has been around 30 years, but upgraded FDCs and launchers able to fire multiple missile types – the AMRAAM, AMRAAM-ER and AIM-9X Block II – keep it relevant. One major improvement has been in the introduction of a multi-missile threat evaluation and weapon allocation capability in the FDC within the past few years.

“That’s where the FDC makes a recommendation for an operator to make a decision around what missile they may want to use against a particular target,” Fry said. “Having multiple missiles is great, but when the system’s clever enough to make recommendations on what the best choice is for that target set, I think that’s been one of the real significant enhancements that’s come into the system.”

Future directions

Asked about future trends, the EOS spokesperson predicted “greater integration” of AI for improved target detection and recognition, including simultaneous tracking of multiple targets such as small, high-speed drones in low-contrast conditions. Another expectation is “more autonomy” in systems to enable faster engagement time, particularly against drone swarms.

Posing the same question to MBDA, a spokesperson told Global Defence Technology that “collaboration and cooperation is key to the future of air defence”, citing examples like ESSI and the Timely Warning and Interception with Space-based TheatER Surveillance (TWISTER) counter-hypersonic project.

EOS also offers a high-energy laser weapon for C-UAS. Credit: EOS

New effectors in the form of directed energy weapon systems are appearing too. As MBDA said: “Directed-energy weapons are already a direction that air defence is taking, becoming complimentary effectors systems.”

MBDA noted that laser-directed energy weapons and radio frequency directed-energy weapons are already modular options in its Sky Warden C-UAS system.

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.