Cover Story

Eye in the sky

As the first line of threat detection, airborne early warning is a must-have capability for the world’s militaries. Gordon Arthur reports.

Australia was the first country to adopt the E-7A Wedgetail. Credit: Gordon Arthur

Acting like aerial quarterbacks, airborne early warning (AEW) aircraft are critical force multipliers as they scan from on high to identify hostile, long-range targets, and simultaneously marshal friendly aircraft.

Additional to airborne battlefield command and control, these versatile platforms perform surface surveillance and even conduct electronic warfare. Of note, older AEW airframes are now coming up for replacement in Nato.

Taking France as an example, the French Air Force operates four Boeing E-3F Sentry aircraft. As their maintenance cost grows, Paris is contemplating accelerating their replacement. Yet what options are available to nations like France as they retire obsolete AEW aircraft, or to others who might be contemplating adopting AEWs for the first time?

The DroneGun Mk4 is a handheld countermeasure against uncrewed aerial systems. Credit: DroneShield

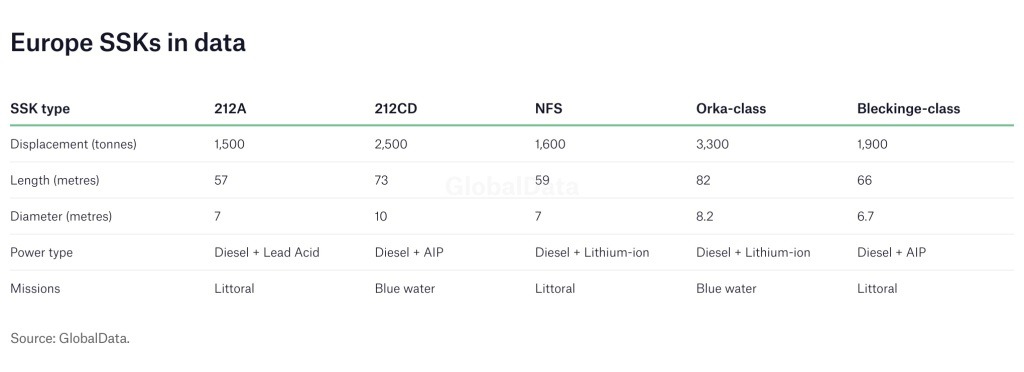

One key programme that will affect by a number of European operators is the evolution of the Type 212A conventional diesel-electric submarine (SSKs) design. Three nations are building on this legacy model in two different variations: first, the German and Norwegian Type 212 Common Design (CD) and second, Italy’s U212 Near Future Submarine (NFS).

It will also be valuable to examine how these changes differ from the capabilities offered by other European SSK designs, including the Dutch Orka class and Swedish Bleckinge-class submarines.

Boeing E-7

Boeing developed the E-7A Wedgetail, for which the Royal Australian Air Force was the launch customer with a fleet of six aircraft. Since then, 737-based aircraft were procured by South Korea and Türkiye too. The UK and US are the latest adherents as they replace decades-old E-7 Sentries, whose days of guard duty are almost over.

The US Air Force (USAF) plans to procure 26 E-7s. Kicking things off, Boeing is building two rapid-prototype E-7As under a $2.56bn contract signed in August 2024. These are to be delivered by FY2028, although they intentionally have “emerging capabilities” omitted.

A number of Nato countries will operate the E-7 aircraft. Credit: Douglas Cliff / Shutterstock

To modernise the platform, via an April request for information, the USAF is canvassing the inclusion of a new radar, electronic warfare equipment and enhanced

communications to create an “Advanced E-7”. Two such examples are sought within seven years, after which other E-7s could be retrofitted with the modifications.

As for the UK, three 737NG aircraft are currently undergoing modification in Birmingham, the first completing its maiden flight in September 2024.

Global Defence Technology asked Boeing what makes the E-7 stand out, and a spokesperson listing three points. First is its allied interoperability. “With the aircraft in service or on contract with Australia, South Korea, Türkiye, the UK and USA – and selected by Nato – its unmatched interoperability benefits a growing global user community for integration in future allied and coalition operations.”

The E-7 platform is less expensive to operate compared to platforms based on small business jets.

Boeing spokesperson

Next, Boeing said the purpose-built E-7A possesses the ability to “talk to joint assets across multiple domains, increasing situational awareness of the battlespace for coalition participants such as fighters, naval assets and ground agencies in the most challenging of operational environments”.

Thirdly, the aerospace giant said a trilateral Australia-UK-US agreement exemplifies the gains that come from collaborative development.

The E-7A contains ten battle manager/mission consoles, but its defining feature is Northrop Grumman’s Multirole Electronically Scanned Array (MESA) top-hat radar offering an unrestricted 360º view. The MESA can dynamically adjust its detection range, so if a threat emanates from a particular direction, more energy can be focused there to extend its detection range.

Boeing claimed too: “The E-7 offers the most resilient, advanced airborne moving target indicator capability available.”

The platform’s radar coverage spans more than four million km² in a standard mission. If that is insufficient, the aircraft can be aerially refuelled to extend its operational range even farther.

One other advantage of the E-7 is its utilisation of 737 airframes. With 9,000+ 737s flying worldwide, supported by 250 global service centres, its commercial DNA lowers operating costs and boosts readiness rates. In fact, Boeing’s spokesperson claimed, “The E-7 platform is less expensive to operate compared to platforms based on small business jets, which require extensive alterations and face more costly, disruptive maintenance regimes.”

E-2D Advanced Hawkeye

A second American entrant in the AEW market is Northrop Grumman’s E-2D Advanced Hawkeye. A company executive told Global Defence Technology that, while the E-2D may look the same as its E-2C predecessor on the outside, it is nonetheless a completely new aircraft internally.

To date, Northrop Grumman has delivered more than 60 E-2Ds for the US Navy’s programme of record of 82 aircraft; it claims a 100% record in delivering on schedule.

The spokesperson said: “We’ve been supporting the navy with next-generation maintenance and sustainment, which are delivered with applications that enhance diagnostics and reduce costs. Predictive maintenance technology improves E-2D readiness.”

The second-largest operator of the E-2D is Japan. Tokyo has 18 units on order, of which ten have been delivered thus far to replace its E-2C fleet. France is the only nation besides the US to operate Hawkeyes from aircraft carriers. Its navy flies three E-2C Hawkeye 2000s, but it has already ordered a trio of replacement E-2Ds; the first started production in December 2024 and is due for completion in 2027.

An older E-2C 2000 Hawkeye belonging to Taiwan. Credit: Gordon Arthur

Northrop Grumman listed three key characteristics of the E-2D. Firstly, its Lockheed Martin AN/APY-9 radar is “designed to provide comprehensive 360º coverage, leveraging the all-weather UHF band to provide unparalleled wide-area surveillance in the most challenging environments”.

Second is the E-2D’s operational flexibility, for it has a relatively small logistical footprint, and is versatile enough to operate from either land or sea.

The final feature of the Advanced Hawkeye is its diverse mission set. In addition to staple airborne command-and-control missions, Northrop Grumman listed roles like defensive and offensive counter-air, integrated air and missile defence, electronic warfare, air traffic control, combat search and rescue, humanitarian relief, border security and counter-drug operations.

The E-2D is not standing still either. Five major upgrades have been implemented to bring improvements in areas like the radar, data fusion, sensor upgrades, counter-electronic attack and satellite communications. Greater automation is also being implemented, meaning tasks such as target tracking, radar fine-tuning and reporting are now largely automated to free up crews for mission-critical jobs. Furthermore, aerial refuelling expands the E-2D’s endurance.

Northrop Grumman described a Block II technology roadmap that reaches well into the 2040s. “Block II will improve connectivity for C2 and create a modular open-systems environment for future technology insertions such as artificial intelligence and machine learning.”

Business jet-based AEW

Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) is another company offering AEW solutions. It can integrate relevant Israeli mission systems into various donor platforms. For instance, Elta’s ELW-2085 radar can be installed aboard Global 6500 or Gulfstream G550 business jets.

Israel, Italy and Singapore operate what the company calls G550 Conformal Airborne Early Warning aircraft. IAI’s latest-generation AEW platform is the Embraer Praetor 600 midsize business jet that boasts an ELW-2096 radar.

Meanwhile, Saab’s AEW offering is called the GlobalEye, this featuring an Erieye Extended Range (ER) radar atop the aircraft fuselage, with customers currently including Sweden and the UAE. The latter received five Bombardier Global 6000-based aircraft, the last handed over in 2024.

Saab’s GlobalEye with Erieye ER radar builds upon successes with earlier models. Credit: Saab

As for Sweden, it ordered two GlobalEyes in mid-2022 and a third in June 2024. These will replace two Saab 340 AEW aircraft promised to Ukraine.

Thomas Lundin, head of marketing and sales, Airborne Early Warning and Control Systems at Saab, pointed out that, because nations do not operate in constant states of war, the GlobalEye can deliver benefits in every situation, including dealing with grey zone or hybrid threats. Additionally, the aircraft carries a Leonardo Seaspray radar optimised for maritime surveillance.

The threat scenario has evolved a lot over the past few years.

Thomas Lundin, Saab

Lundin said the GlobalEye has evolved over time. Although unable to disclose specific details, he did say, “Saab invests and works with spiral developments around sensor performance and associated software technologies that will support AEW&C-related missions. We’ve also demonstrated our ability to add new operational capabilities to customers’ aircraft.”

The GlobalEye’s development will continue too. Lundin revealed: “The threat scenario has evolved a lot over the past few years, and Saab’s solutions have followed this development, creating new assets and capabilities that address those threats with passive and active sensor development. For instance, the GlobalEye can observe and detect drones. The Erieye ER radar expands the detection distance for small, slow and low-flying objects.”

Saab is pitching the GlobalEye for Canada’s current AEW requirement, the first time Ottawa has sought these sophisticated assets. Saab is offering its Erieye ER radar mounted on Canadian-manufactured Bombardier Global 6000/6500 airframes

Opposing players

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Northrop Grumman should be pleased that China slavishly copied its E-2 Hawkeye’s external form to create the KJ-600. Once development is completed, this will be China’s first AEW aircraft to operate from catapult-equipped aircraft carriers.

Whilst on the topic of China, the country is also developing a Y-20B aircraft-based AEW prototype fitted with a radome. Spotted in flight testing last December, this large platform will presumably become China’s mainstay AEW platform and will supplement smaller, third-generation, turboprop systems like the KJ-500.

The KJ-500 AEW aircraft is based on the Y-9 turobprop airframe. Credit: Gordon Arthur

Even North Korea is getting in on the AEW act. First noticed in late 2023, Pyongyang added a radome to a single Il-76 aircraft. If the project is successful, North Korea can use its homegrown asset to monitor “enemy” activity across the Korean Peninsula, as well as to better track its own missile tests.

Operational practicalities

When aerial conflict between India and Pakistan broke out from 7-10 May, AEW aircraft were an important part of the equation. It is impossible to verify many details of the cross-border clash, but parochial media widely claim that India destroyed two Pakistani AEW aircraft, one in the air and another on the ground. If true, these would have been Saab 2000 Erieyes.

Given the threat level that India faces along its borders with Pakistan and China, Delhi actually has a serious shortage of AEW platforms. It is seeking to address this with future systems based on Embraer ERJ-145 and Airbus A319 airframes.

Regardless, this recent India-Pakistan conflict underscored the important role that specialised, and expensive, AEW platforms play in modern combat. Not only that, but they are priority targets for an adversary too and so must be suitably protected.

The US is by far the largest spend on nuclear submarines. Credit: US Navy

Country | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | 2033 | 2034 |

Australia | 3,582 | 3,586 | 3,590 | 3,594 | 3,613 | 3,622 | 6,183 | 6,207 | 6,216 | 6,239 | 6,380 |

China | 2,607 | 2,802 | 3,040 | 3,081 | 3,174 | 3,291 | 3,396 | 3,603 | 3,664 | 3,710 | 4,316 |

India | 2,320 | 2,533 | 3,675 | 2,457 | 2,526 | 2,639 | 2,741 | 2,873 | 2,958 | 3,350 | 3,560 |

Russia | 2,701 | 2,893 | 2,973 | 3,334 | 3,458 | 3,106 | 3,235 | 3,405 | 2,958 | 3,487 | 3,942 |

US | 16,957 | 18,037 | 18,522 | 18,607 | 18,137 | 18,898 | 18,898 | 19,643 | 19,876 | 22,592 | 23,730 |

Lisa Sheridan, an International Field Services and Training Systems programme manager at Boeing Defence Australia, said: “Ordinarily, when a C-17 is away from a main operating base, operators don’t have access to Boeing specialist maintenance crews, grounding the aircraft for days longer than required.

“ATOM can operate in areas of limited or poor network coverage and could significantly reduce aircraft downtime by quickly and easily connecting operators with Boeing experts anywhere in the world, who can safely guide them through complex maintenance tasks.”

Boeing also uses AR devices in-house to cut costs and improve plane construction times, with engineers at Boeing Research & Technology using HoloLens headsets to build aircraft more quickly.

The headsets allow workers to avoid adverse effects like motion sickness during plane construct, enabling a Boeing factory to produce a new aircraft every 16 hours.

Elsewhere, the US Marine Corps is using AR devices to modernise its aircraft maintenance duties, including to spot wear and tear from jets’ combat landings on aircraft carriers. The landings can cause fatigue in aircraft parts over its lifetime, particularly if the part is used beyond the designers’ original design life.

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.