Cover Story

Dangerous waters: Europe’s subsurface crisis

Europe is not limited to littoral defence, but evolving to support a broader collective forward maritime posture and deterrence strategy. John Hill reports.

A Type 212A submarine developed by thyssenkrupp Marine Systems. Credit: TKMS

European navies are in a transition period in the subsurface domain as conventional submarine operators move to gradually replace existing boats with newer, more capable, platforms. However, with the deteriorating security state on the continent, any delays could be exploited as Russia watches on.

“We are navigating very dangerous waters,” said the Chief of the Royal Norwegian Navy, Rear Admiral Oliver Berdal, as he opened the 2025 Undersea Defence Technology (UDT) conference in March.

“There have been many incidents over the last few years that have shaken us up,” he added, with incidents such as the increasing sabotage of critical undersea infrastructure (CUI) in the Baltic region and the destruction of Nordstream gas pipelines in 2022 to the Estlink sabotage at the end of 2024.

The revelation that Russian sensors, either captured or washed up on British shores, as reported by The Times, demonstrates the immediacy of the threat, and the reality that the UK and its European allies are already caught up in a grey-zone conflict beneath the surface.

The timing is of these incidents is also less than deal. European navies are undergoing a transition period in which new generation submarines will not enter service until the end of the decade at least.

The DroneGun Mk4 is a handheld countermeasure against uncrewed aerial systems. Credit: DroneShield

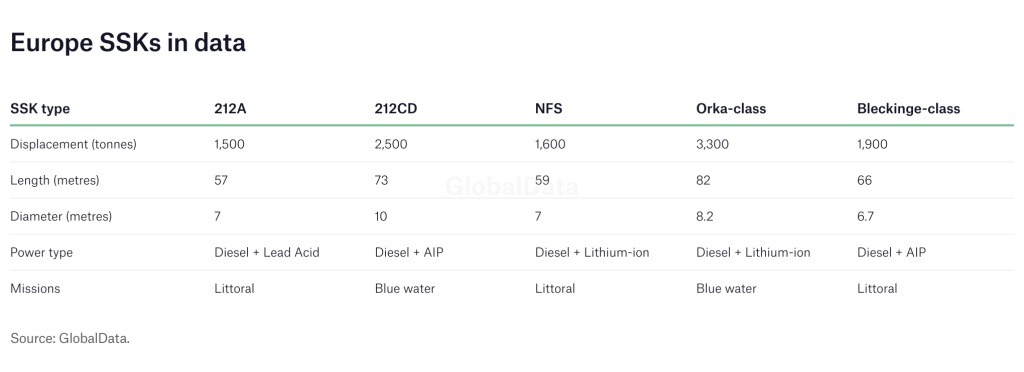

One key programme that will affect by a number of European operators is the evolution of the Type 212A conventional diesel-electric submarine (SSKs) design. Three nations are building on this legacy model in two different variations: first, the German and Norwegian Type 212 Common Design (CD) and second, Italy’s U212 Near Future Submarine (NFS).

It will also be valuable to examine how these changes differ from the capabilities offered by other European SSK designs, including the Dutch Orka class and Swedish Bleckinge-class submarines.

Germany and Norway

The Type 212CD will succeed the original 212A in the German Navy as well as Norway’s ageing Ula-class. Ten submarines (six German and four Norwegian) are currently in the pipeline, but this order will increase to 12 boats between the two partners pending parliamentary approval in Norway later this year.

At the UDT event, two speakers, representing their respective navies, delivered an update on 212CD where they confirmed that the first boat is already under construction. The initial submarine will enter service in 2029.

Type 212CD is the sum of a combination of the two navies’ requirements but modelled on 212A. Germany and Norway have signed up to 50 technical agreements in formulating their final and approved Common Design.

The most noticeable change in the 212CD compared to its forebear is its size: the displacement is 2,500 tonnes – a 65% increase from the 212A at 1,524 tonnes.

Computer generated image of the future German/Norwegian Type 212CD SSK. Credit: Thyssenkrupp

New generation advancements feature unique structures, such as the boat’s diamond-shape to reduce target echo strength; modern combat systems; great firepower and superior stealth technology including the fuel cell based air-independent propulsion (AIP).

The two nations are also building infrastructure to support the lifecycle of the boats, including a common maintenance facility at Haakonsvern Naval Base in Bergen, Norway which can support up to nine submarines at once. It was hinted that more capacity will be established in Wismar, Germany as well in the coming years.

All this infrastructure is built with more partners in mind, the two speakers emphasised, so other partners are allowed to join the programme but the design cannot be changed.

There is strategic value to the joint procurement of standard platforms and interdependent industrial partnerships within Europe. Common approaches will make the European region more competitive in the global market, especially as the European Union pursues strategic autonomy as the world, politically, divides ever further apart.

Italy

Europe’s defence programme manager OCCAR is trusted with monitoring the development and delivery of the Italian Navy’s U212 NFS, of which the service has acquired four submarines to be delivered between 2029 and 2032.

The first two submarines were contracted in February 2021, with an option for two additional units. The option for the third submarine was exercised in December 2022, and the contract for the fourth was signed in June 2024.

A notable advancement of NFS is that the SSK is powered by a lithium-ion battery – made in Italy – rather than lead acid, which powers its forebear the 212A. An OCCAR spokesperson told Global Defence Technology that this provides 20% more available energy and means less periodical maintenance. Depending on the profile of the mission, this means that NFS can submerge for up to 30 days.

Section 30’ of the U212 NFS under construction. Credit: OCCAR

In essence, this battery change allows the NFS to do more than the Navy has done before underwater.

In December 2024, Fincantieri completed final operational tests of the lithium-ion battery system. Five months earlier, a lithium-ion battery manufacturing facility was established under the auspices Power4Future, a Fincantieri subisidiary, based in the Lazio region.

This indicates Italy’s strategic ambitions to sustain its own submarines, ensuring the Italian Navy can operate when needed, and thus less reliant on other nations at a time of protectionism and disruption of global supply chains.

Outside the 212 family

Ironing out details of the common approach has it limits, as the 212CD duo testified during UDT, citing differences of submarine safety as one area that “could have led to a separation”, with compromises made to create an SSK design that meets both users’ requirements.

Originally, the Netherlands had formally opted for the 212CD until its priorities shifted. As a result, Thyssenkrupp claimed its bid had been unjustly invalidated. Now, the Netherlands are pursuing a Dutch-led programme with the Orka-class, a French Naval Group design, which will replace its legacy Walrus-class between 2033 and 2038.

“The Orka-class is designed for long-range missions and expeditionary operations as well as operations in coastal waters,” said a spokesperson within the Royal Netherlands Navy (RNN). “The U212CD is primarily suited for coastal operations, e.g. submarine operations in the Baltic area and North Sea.”

While the Orka is relatively larger than 212CD, the Common Design does still have expeditionary capabilities as the submarine can serve as a blue water boat, somewhat contrary to the Dutch assessment.

Meanwhile, the RNN elaborated that the Orka was selected to exercise strategic influence; large and precise maritime striking power; worldwide collection, analysis and sharing of intelligence and special operations.

Artist’s impression of the Orka-class SSK. Credit: Dutch Ministry of Defence

Sweden, a key player in the Baltic Sea, is pursuing Saab’s A26 SSK model, the Bleckinge class. This SSK is slightly smaller than its modern counterparts, and similarly plays a littoral and blue water role.

In the Baltic context, the Bleckinge class has a unique feature in its X-rudder configuration, with four independently controlled surfaces that provide high manoeuvrability.

This will prove to be a much-needed capability in seabed warfare in the highly contested Baltic Sea, for which the boat was specifically designed.

Kandlikar Venkatesh, a defence analyst at GlobalData, emphasised the dual approach of European SSKs: “Europe’s strategy for SSKs implies a two-way approach of securing dominance in its coastal and confined maritime zones, while building credible capacity for operations in open-ocean theatres.

“Europe’s SSK fleet (Type 212CD, NFS, and others) is ensuring they are not limited to littoral defence, but evolving into a mobile, interoperable and increasingly autonomous force designed to support a broader European forward maritime posture and deterrence strategy.

“Whether operating silently in the Baltic or conducting extended patrols in the North Atlantic, these submarines embody Europe’s commitment to credible, modern undersea warfare in an increasingly contested maritime environment.”

This is a race

Hans Hoyer, sales director, DroneShield

The US is by far the largest spend on nuclear submarines. Credit: US Navy

Country | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | 2033 | 2034 |

Australia | 3,582 | 3,586 | 3,590 | 3,594 | 3,613 | 3,622 | 6,183 | 6,207 | 6,216 | 6,239 | 6,380 |

China | 2,607 | 2,802 | 3,040 | 3,081 | 3,174 | 3,291 | 3,396 | 3,603 | 3,664 | 3,710 | 4,316 |

India | 2,320 | 2,533 | 3,675 | 2,457 | 2,526 | 2,639 | 2,741 | 2,873 | 2,958 | 3,350 | 3,560 |

Russia | 2,701 | 2,893 | 2,973 | 3,334 | 3,458 | 3,106 | 3,235 | 3,405 | 2,958 | 3,487 | 3,942 |

US | 16,957 | 18,037 | 18,522 | 18,607 | 18,137 | 18,898 | 18,898 | 19,643 | 19,876 | 22,592 | 23,730 |

Lisa Sheridan, an International Field Services and Training Systems programme manager at Boeing Defence Australia, said: “Ordinarily, when a C-17 is away from a main operating base, operators don’t have access to Boeing specialist maintenance crews, grounding the aircraft for days longer than required.

“ATOM can operate in areas of limited or poor network coverage and could significantly reduce aircraft downtime by quickly and easily connecting operators with Boeing experts anywhere in the world, who can safely guide them through complex maintenance tasks.”

Boeing also uses AR devices in-house to cut costs and improve plane construction times, with engineers at Boeing Research & Technology using HoloLens headsets to build aircraft more quickly.

The headsets allow workers to avoid adverse effects like motion sickness during plane construct, enabling a Boeing factory to produce a new aircraft every 16 hours.

Elsewhere, the US Marine Corps is using AR devices to modernise its aircraft maintenance duties, including to spot wear and tear from jets’ combat landings on aircraft carriers. The landings can cause fatigue in aircraft parts over its lifetime, particularly if the part is used beyond the designers’ original design life.

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.