Feature

Japan: reemergence of an Asia-Pacific power

By 2027 Japan plans to take “primary responsibility” for national defence against overseas invasions and is seeking to expand its stand-off strike capabilities. Richard Thomas reports.

Japan’s military build-up has been accelerating in recent years. Credit: Josiah_S / Shutterstock

After decades of imposed and subsequently adopted peaceful isolationism, Japan is waking up to a series of new challenges in the western Asia-Pacific region, one in which China is seeking to claim for its own in an emergent multi-polar global order.

Detailing key defence priorities in its new Defence White Paper, published on 12 July, Japan includes the nuclear threat posed by North Korea and ongoing concerns around Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and, in a regional specific matter, its occupation of the Kuril Islands chain in the northwestern Pacific, which are also claimed by Tokyo.

The new defence paper reaffirmed Tokyo’s commitment to defence spending, stating that Japan would take “necessary measures” to ensure the budget for “fundamental reinforcement of defence capabilities and complementary initiatives” reaches 2% of FY2022 GDP levels by FY2027. At this level, funding was calculated to be approximately ¥11 trillion ($69.6bn) by 2027.

GlobalData forecasts from 2023 indicate that Japan’s total defence expenditure was anticipated to value $85.9bn in 2028, owing to the need to “adequately finance its own national defence capabilities”.

Japan will acquire hundreds of Block IV Tomahawk cruise missiles from the US. Credit: US Navy

In addition, Japan scrapped its long-standing 1% GDP ceiling for annual defence spending and publicly stated its desire to hit the 2% benchmark over the next decade. Current estimates put Japan’s defence spending at around 1.6% of GDP.

Between 2024-2028, Japan’s defence spending was forecast to increase from $70.3bn to $85.9bn in over the period, as it embarks on a wide-ranging recapitalisation of its military, including the development and addition of new naval platforms and stand-off attack munitions.

Detailing the potential threats posed by China and Russia, the White Paper revealed that in FY2023, Japan’s Air Self-Defence Force fighters were forced to scramble 669 times to intercept encroaching aircraft, the vast majority of them conducted by China (479 instances) and Russia (174 instances).

Japan’s defence build-up programme

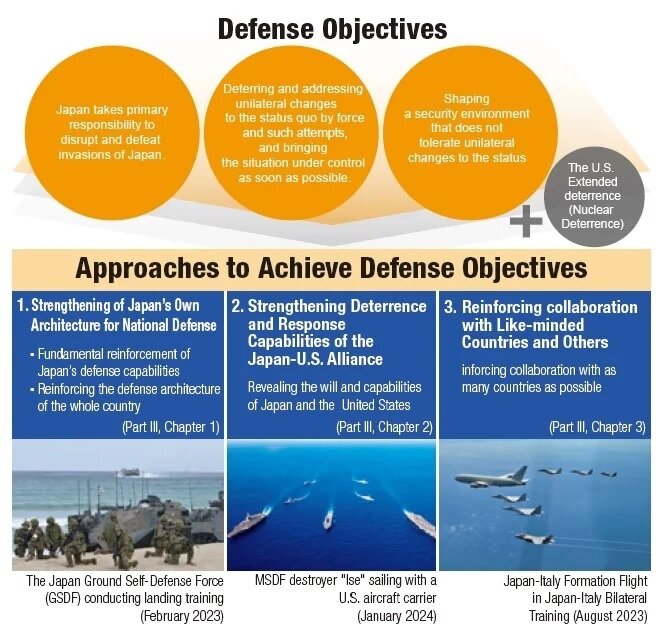

Initiated in 2022, Japan’s Defence Build-up Programme (DBP) is a multi-year process intended to provide the country with the required capabilities determined necessary to defend its own interests, in areas such as space, cyber, electromagnetic domains, and greater integration of military services.

Included in this was the target that by 2027 Japan would be able to take “primary responsibility for dealing with invasions against its nation”, as well as the ability to “disrupt and defeat such threats while gaining support of its ally and others”.

The realignment of the USFJ is a crucial initiative

Japan Defence White Paper

This commitment to independent self-defence capability was reiterated in the 2024 White Paper, which points to a shifting Japanese relationship with the US, still declared a cornerstone of its defence policy, but now increasingly spoken of in terms of military partners rather than acting as a client state serving simply to host the immense US military forces deployed in Japan.

“While the presence of the US Forces in Japan (USFJ) functions as a deterrence, it is necessary to make efforts that are appropriate for the actual situation of each area to mitigate the impacts of the stationing of the USFJ on the living environment of local residents,” the White Paper stated.

“The realignment of the USFJ is a crucial initiative to mitigate the impact on local communities, including those in Okinawa, while further strengthening the deterrence and response capabilities of the Japan-US Alliance.”

The US maintains more than 50,000 military personnel in Japan, where it has had a military presence since the end of WWII, with Japan hosting large air force and naval bases, with Yokosuka the home of the US Navy’s 7th Fleet.

Credit: Government of Japan

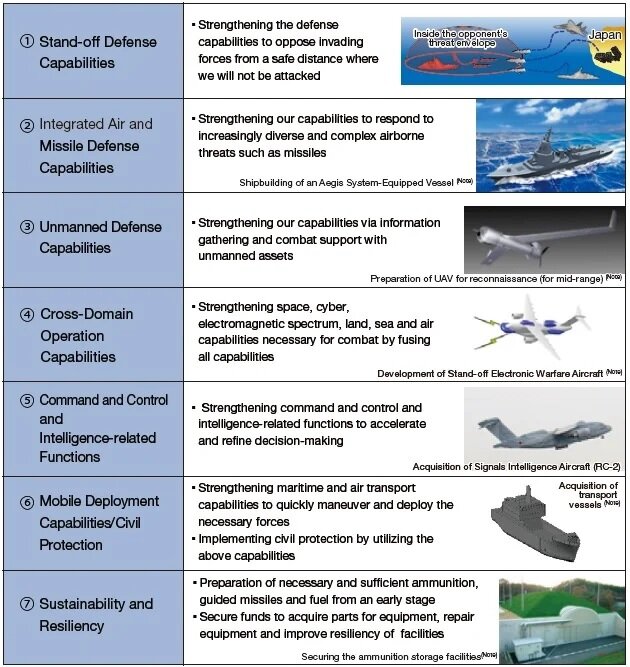

Other elements including the ability to utilise stand-off weapons, originally set at being introduced in the 2030s, have been brought forward, as threats continue to proliferate.

The White Paper stated that total expenditure needed to achieve the level of defence buildup sought by the DBP for five years from FY2023 to FY2027 amounts to approximately ¥43 trillion.

Tokyo speeds up Tomahawk acquisition

Among Japan’s military acquisition efforts is a focus on stand-off strike capabilities, such as its Tomahawk cruise missile programme.

[Japan] will fundamentally reinforce its stand-off defence capabilities

Japan Defence White Paper

The Defence White Paper restated the intention to speed up its acquisition of Tomahawk cruise missile as well as the deployment of the upgraded ground-launched Type-12 anti-ship missile, bringing forward the timelines for both programmes from FY2026 to FY2025.

In a programmatic outline of future platforms and capabilities, the defence paper stated that Japan “will fundamentally reinforce its stand-off defence capabilities to respond from outside the threat zone, including anti-aircraft missiles, against naval vessels and landing forces that invade Japan, including its remote islands”.

Credit: Government of Japan

Included in this was the “deployment on Upgraded Type-12 SSM (surfaced-launched variants)” as well as the “acquisition of US-made Tomahawks”, which was to be accelerated by one year, starting in FY2025, to “promptly secure sufficient capabilities”.

Aegis System Equipped Vessels

Elsewhere, and in a bid to “strengthen the integrated air and missile defence capabilities”, Japan’s Ministry of Defence will start construction of the Aegis System Equipped Vessels, an anticipated class of two large surface warships able to conduct ballistic and potentially hypersonic missile defence operations.

In the White Paper’s forward, Japan Minister for Defence Kihara Minoru stated that the start of construction of the Aegis System Equipped Vessels would be “expedited” in order to enable Japan to “defence [itself] from increasingly sophisticated ballistic missile and other threats”.

Low-res images of the ASEV warships were released in Japan’s 2024 Defence White Paper. Credit: Government of Japan

Potentially linked to this is a joint Japan-US programme to develop a “Glide Phase Interceptor (GPI) guided missile to counter Hypersonic Glide Vehicles (HGVs)”, the White Paper stated, as well as the ongoing procurement of SM-3 Block IIA, SM-6, PAC-3MSE missiles.

GlobalData’s Global Missiles & Missile Defense Systems Market Forecast 2023-2033 report reveals that Japan is expected to spend approximately $8.9bn to procure various types of missiles, including the procurement of interceptor-category missiles such as the AIM-120C-7, RIM-161D SM-3 Block-2, RIM-66 Standard, RIM-116 RAM Block 2, and RIM-174 Standard ERAM, all of which will be procured from the US.

As part of this effort, Japan has earmarked $1bn for the development of the GPI munition.

Japan to promote uncrewed systems

Additional capabilities that Japan is seeking to integrate into its forces structure include uncrewed assest that are able to operate for extended periods, including the development of uncrewed amphibious vehicles that can “land on any shore of islands and perform tasks such as transporting supplies from the sea to the vicinity of troops”.

Further, Japan will establish a new formation to improve deployment capabilities in its southwest region, under the tentatively named Self-Defense Forces Maritime Transport Group, as a joint force, along with the acquisition of “maneuver support vessels and transport helicopters”.

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.