Earning AI trust in defence simulations

Modern defence training simulations rely on artificial intelligence to make the synthetic elements behave realistically. If they do not, participants lose trust, and the exercise fails to meet its objectives. CEO and co-founder of distributed computing specialist Hadean Craig Beddis explains how to attain trust when using AI to meet defence needs.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a concept as old as computers themselves, with Alan Turing’s mechanical devices first displaying the fundamental properties behind processing information. Since then, AI has developed to provide us with insight in a vast number of ways.

From helping us understand the building blocks of life to optimising our web searches, AI is everywhere in society. While science fiction examples such as Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey paint a terrifying but surely exaggerated vision of the future of AI, serious questions around AI’s morality, bias and discrepancies face us today.

It's wrong to assume that AI in most of its forms displays its own deductions. Though it may process the information by itself, its logical algorithms display nothing more than the ones its creator intended. Meaning that among the numerous successful analyses, the flaws of a lack of human ethics and judgement equally permeate AI. The extent of these problems became a hotly-discussed topic recently, with several prominent examples having come to light.

Algorithms used in hiring systems, for example, are often based on employment data that is out of date. This caused several demographic biases to come to fruition. But even ones created from modern data are not exempt. Facial recognition software, for example, has been shown to often favour particular facial types usually because the creators tend to be of the same type.

Trust in defence training AI

These issues ultimately culminate in a problem of trust around AI. If systems are only as good as their maker, then how can we be sure the results and decisions reached are not tainted by a potential initial flaw in the inventor? As with every industry, these questions are of paramount importance for defence and the use of AI in training simulations.

These issues drive a lack of trust in AI within these simulations, particularly for NATO

The high complexity and fidelity of simulations today undoubtedly provided a key advantage in training and planning exercises. However, if the AI used is unsound, then this could lead to several problems. Personnel may be training within synthetic environments where enemy units behave inaccurately compared with how they would in the real world. Or wargames that provide reactionary AI tactics for commanding officers may lead to future decisions being poorly informed.

These issues drive a lack of trust in AI within these simulations, particularly for NATO. NATO’s steady approach to its use of AI has led it to often be accused of lagging behind in this area, despite historically driving technological innovation.

These thoughts were echoed by Jens Stoltenberg, NATO’s Secretary-General, who told the Financial Times: “For decades, NATO allies have been leading when it comes to technology, but that’s not obvious anymore. We see China especially investing heavily in new, disruptive technologies like artificial intelligence, autonomous systems and big data.”

Latency risk

Latency regarding the adoption of artificial intelligence also raises the problem of who may exclusively use it. While trusting AI in defence is difficult, without a concerted effort to improve its use, you risk leaving this as a privilege for other militaries. With the speed of action being such an imperative in defence today, the particular advantages that AI offers in this realm are far too beneficial to ignore.

Speed has been the focus of much of the modernisation of militaries, with technology both alleviating arduous tasks and providing rapid data analysis. At a command level, if an optimum strategy can be derived quicker, it may offer benefits such as reducing the number of casualties in time-sensitive scenarios.

At a lower level, the increasing speed of deployment and action among units has similar beneficial outcomes. In several isolated instances, AI and autonomous systems have already been used to speed up command and control functions to great effect. But in today’s world, multi-domain operations dominate defence training, meaning AI needs to be ready to integrate with this new form of warfare.

// T.J. Pope is Honeywell’s senior director, military turboshaft engines. Credit: Honeywell

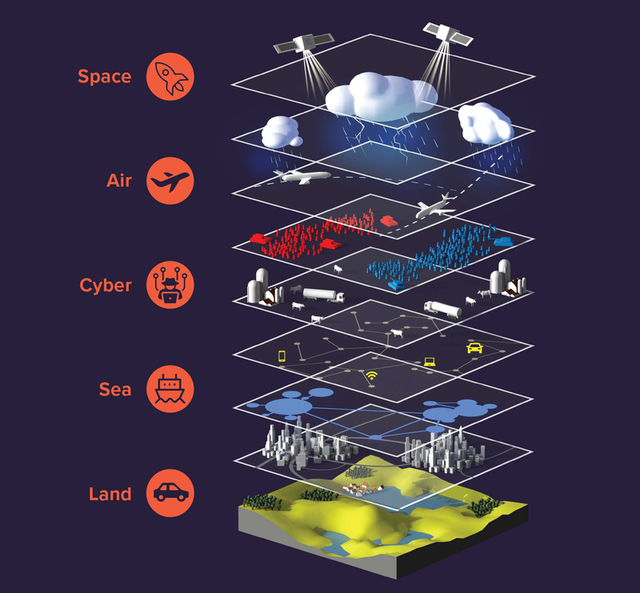

// Caption: Multi-domain operations dominate defence training. Credit: Haden

Multi-domain operations have stretched far beyond the historical air-land-sea and now include cyber, space and psychological factors. It has led to an irregular and unpredictable form of warfare as it has grown in its complexity, often making the correct course of action difficult to determine.

Speed in analysis, therefore, has become essential to navigating these new waters and regaining the strategic upper hand. Data that can inform autonomous systems in an interoperational manner is the key to this, but this has its own difficulties relating to its processing.

These new domains changed the task of interpretation that ultimately presents an entirely new challenge. Data is generated through an increasing number of disparate sources. Furthermore, the variation in the type of data is also increasing. This is presenting a computational challenge that legacy IT platforms struggle to deal with.

Simulating complexity of warfare

Without a sufficient model, there is no reliable way to reveal unexpected circumstances in the complexity of modern warfare. In contrast, advancement in distributed technologies offers a solution. Batches of simulations can be run in parallel to speed up analysis.

Combine this with high fidelity environments and real-time data streaming, simulations can be adapted and up to date insight can be derived. With the cloud offering a platform to translate all this information, the problem remains of how we ensure trust in the analysis our AI performs.

Trustworthy AI begins with designers that have the correct ethics, targets and responsibilities in mind

Achieving this starts at the core of the creation process, where the correct culture and operating structure nurtures the correct approach to creating AI. Trustworthy AI begins with designers that have the correct ethics, targets and responsibilities in mind.

Workshops centred around these goals help eliminate bad habits, identify negative feedback loops and propagate discussions on key data sets and ideas that help build a more trustworthy AI. They encourage questions both about the purpose of the AI but also about its other potential effects that should be considered.

Defence organisations can also make use of industry tools designed for eradicating common mistakes in AI development, which are increasing in number. On top of this, building the correct frameworks into your organisation itself for managing AI development will also lead it to be more trustworthy.

Creating roles that manage and critique how AI is created can achieve this by continuously testing and measuring its activity. Attainment of trust in AI in defence simulations will lead to modernised militaries that can prepare for every scenario in a complex battlespace.

// Main image: Craig Beddis is CEO and co-founder of distributed computing specialist Hadean. Credit: Hadean

Simulation