Feature

Asia-Pacific uncrewed: rising to the surface

Uncrewed maritime vehicles are a growing part of a nation’s naval force structure in the Asia-Pacific region, typically used to perform the dull, dirty, and dangerous duties required for persistent maritime patrol. Gordon Arthur reports.

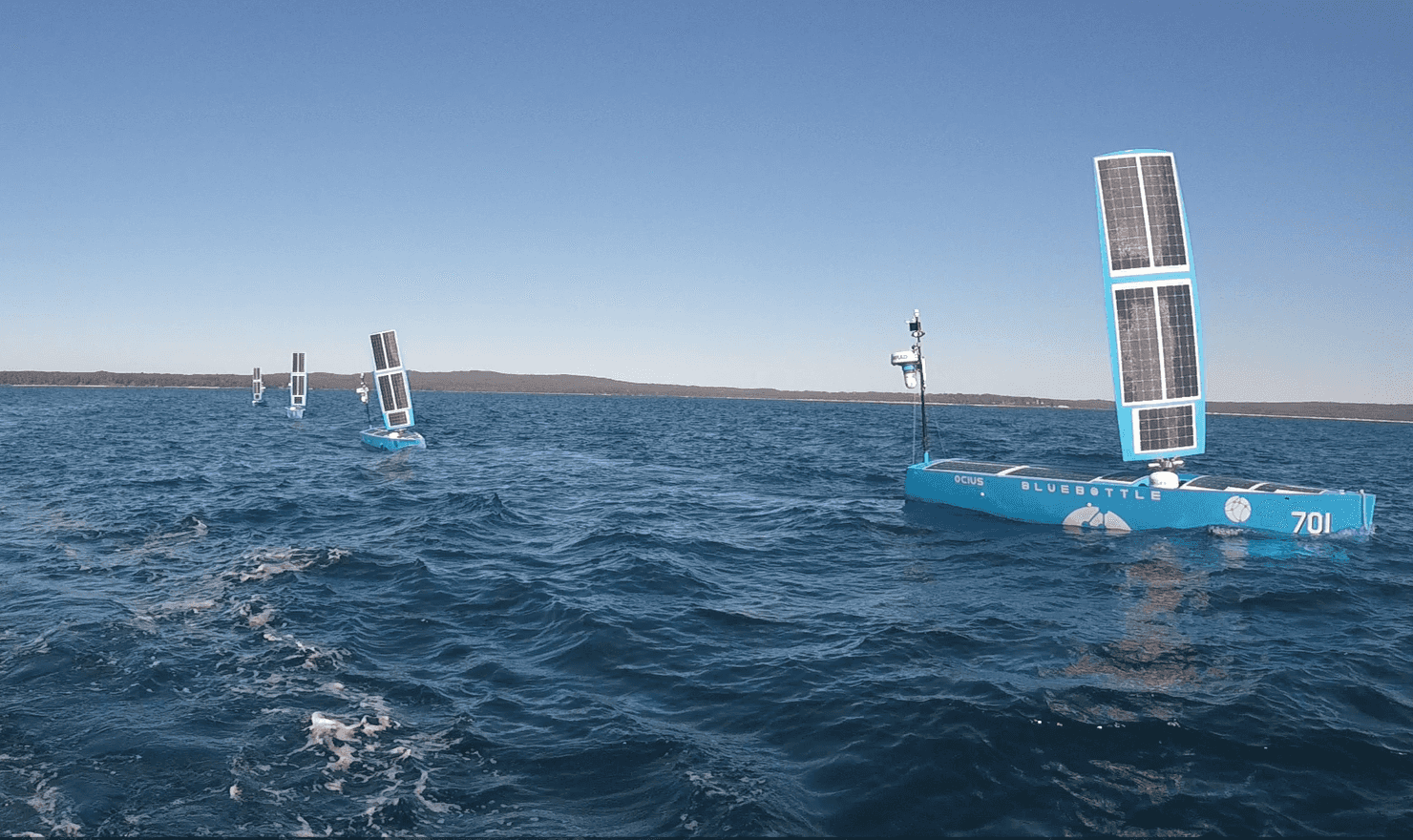

Four of the Royal Australian Navy’s new Bluebottle USVs are seen taking part in an exercise in Jervis Bay in May. Credit: Ocius Technologies

The general understanding of uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) has been buoyed by publicity covering Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, unmanned maritime vehicles (UMVs) are growing steadily in favour too, although their uptake for a wider range of military use is lagging behind that of UAVs.

UMVs can be categorised into two main types: uncrewed surface vehicles (USV) and uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUV). GlobalData estimates that USVs will be the dominant segment, representing 69.1% of the global market over the coming decade. Interestingly, USVs gained a higher profile after Ukraine used “kamikaze” USV swarms to attack Russia’s Sevastopol naval base.

GlobalData forecasts that the global military UMV market, currently valued at $1.3bn, will expand at a compound annual growth rate of 9.52% over the coming decade. At this rate, it is expected to reach $3.2bn in 2033, worth a cumulative $24.9bn.

In a regional breakdown of the above predictions, Europe should be the leading buyer of UMVs with a share of 39.5%. The second strongest regional market is predicted to be Asia-Pacific with 25.2%, and then North America with 16%.

Customers in the Asia-Pacific region are not only buying UMVs from established European and North American manufacturers, but they are also proving innovative as they develop their own unique vessels to suit domestic needs.

Artificial intelligence (AI), energy management developments and sensor networking will all expand the utility of UMVs. Mine countermeasures (MCM) is a common use of USVs, but customers are showing interest in USV swarms, as well as expendable explosives-laden vessels.

Australia looks to private sector development

In Australia, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) has been investing in indigenously developed persistent USVs able to patrol the vast waters surrounding the continent, and to monitor trade routes, shipping and marine resources. Ocius Technologies delivered the fifth and final Bluebottle to the RAN on 8 June, after receiving a $3.3m contract in November 2022. This batch was on top of nine hulls delivered earlier.

Propelled and powered by solar, wind and wave energy, Bluebottles are 6.8m-long craft able to carry a 600kg payload, including sonar arrays.

Such persistent USVs can stay at sea for months, and another vendor is US-based Saildrone. It is cooperating with Austal Australia to manufacture Surveyor USVs in the latter’s shipyard. This move is logical, since Saildrone already employs Austal USA to manufacture Surveyor 20m-long aluminium hulls. The ability to build them in Australia will benefit regional customers, as it reduces transportation costs.

Adam Watters, program manager at Saildrone, commented on the company’s USVs: “We’ve seen tremendous growth over recent years. Saildrone is scaling production rapidly, particularly with the Voyager and Surveyor classes, to meet the demands of customers globally.”

A Surveyor long-endurance and persistent USV from US manufacturer Saildrone sails into Hawaii’s harbour after a long voyage. Credit: Saildrone

However, challenges abound for such craft. Watters noted: “The open ocean is unforgiving, especially when conducting extreme endurance operations. Saildrones are required to operate in extreme heat and cold, hurricane-force winds, high sea states and ripping currents. All of this requires Saildrone vehicles to be robust, reliable and have critical redundancies on core systems to ensure our customers get the data they need regardless of the conditions.”

Such USVs have attendant advantages. “[They] are not a replacement for crewed ships but, instead, augment manned assets to provide wide-area coverage and persistent presence,” Watters explained. “By taking monotonous or repetitive tasks away from crewed vessels, USVs can free up ship time for higher-value tasks that only humans can do, such as interdictions and enforcement. Providing persistent observations 24/7 with AI-enabled detections and classification, Saildrone is a vital tool to expand the capabilities and area of coverage for any navy/law enforcement agency.”

This scaled mock-up of the NSM-equipped USV, being developed for the Indonesian Navy, was shown at LIMA 2023. Credit: Gordon Arthur

In addition, Austal Australia is engaged in a Patrol Boat Autonomy Trial for the RAN, where it has converted a decommissioned Armidale-class patrol boat into a USV. L3Harris is aiding with autonomous technologies on Sentinel. Austal explained: “The trial will establish robotic, automated and autonomous elements on a patrol boat, providing a proof-of-concept demonstrator for optionally crewed or autonomous operations for the RAN into the future. The trial will also explore the legal, regulatory pathways and requirements of operating an autonomous vessel at sea.”

The original schedule will see Sentinel commence sea trials in October.

East Asia showcases innovation

Moving to South Korea, LIG Nex1 has been developing the Sea Sword USV for some time, the latest evolution being the 8m-long Sea Sword-5. The Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN) is considering it for operation from future command ships that will carry UAVs, USVs and UUVs. The Sea Sword-5, armed with a remote-controlled weapon station (RWS), could provide force protection. Hyundai Heavy Industries and Hanwha Ocean have both presented proposals for this upcoming requirement that the ROKN unveiled last year.

Hanwha Systems is developing two USVs for the ROKN, with concepts displayed at June’s MADEX naval exhibition in Pusan. These are the 12m-long Sea Ghost that can also command and control up to four smaller armed M-Searcher USVs.

Japan is perhaps not exploiting unmanned technologies as much as its neighbours, but it has recently introduced a USV on its Mogami-class frigates. Each 3,900-tonne warship will carry an optionally crewed vessel manufactured by Japan Marine United (JMU), whose roles include MCM and mine-laying. The 11-tonne USV features a retractable hull dome, side-scan sonar (mounted or towed), multi-beam echo sounder and a launcher for UUVs. Significantly, this is the first time Japanese warships have carried UMVs in this fashion.

We’re seeing rapid demand growth for the use of USVs to gather all types of data

- Adam Watters, program manager at Saildrone

It is difficult to determine how widely China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has adopted USVs. However, a special USV facility near Dalian is evident in satellite imagery. The PLAN is testing large USVs at this site, probably the JARI (standing for Jiangsu Automation Research Institute). The PLAN began testing the 15m-long JARI in 2020, and it can be armed with a 30mm cannon, lightweight torpedoes or even a small 2x4 missiles vertical-launch system. That means air defence, anti-ship and anti-submarine missions could be within its capability.

Another USV, around 21m long, has also appeared at the auxiliary test base, perhaps a development of the JARI. This shows that the PLA is actively exploring uncrewed technologies and developing concepts of operation.

Certainly, there is no shortage of innovation. China launched a futuristic-looking 88.5m-long, 2,000-tonne drone mothership in Guangzhou on 18 May 2022. Christened Zhu Hai Yun, it can carry up to 50 UUVs, USVs, and UAVs. Although built with marine research in mind, experience gained with this vessel will surely steer future Chinese military autonomous-vessel efforts.

A scale model of the JARI from China, which has been marketed to international customers. Its status within the PLAN is uncertain. Credit: Gordon Arthur

China is also establishing the world’s largest test facility for UMVs. Located near Zhuhai, the Wanshan Marine Test Field covering 771.6km² will be developed in phases.

Elsewhere, Beikun Intelligent Technology dispatched its 200-tonne trimaran-hulled USV on its first seagoing foray in June 2022. Chinese commentators said this 40m-long vessel – resembling the US Navy’s Sea Hunter – could permit new tactics such as distributed operations and swarm attacks for the PLAN.

Another player is Yunzhou Intelligence Technology in Zhuhai, which debuted its L80 USV in 2019. Its narrow-aspect wave-piercing trimaran hull form measures 12.12m long. In 2018, Yunzhou demonstrated 56 USVs operating in a swarm. Furthermore, last year at the World Defense Show in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) unveiled a scale model of a new 340-tonne combat USV measuring 58m long and with a conceptual 4,000nm range.

Southeast Asia: littoral focus?

At May’s LIMA 2023 exhibition in Malaysia, Indonesia was the centre of an innovative USV concept. Indonesian shipbuilder PT Lundin is currently constructing a 33-tonne high-speed USV for the Indonesian Navy, while the state-owned shipbuilder PT PAL will develop a future mothership measuring 100m long able to carry four such USVs. The two shipbuilders signed a cooperation agreement with Kongsberg Defence & Aerospace on 3 November 2022.

The second strongest regional market for UMV up to 2033 is predicted to be Asia-Pacific with 25.2% share

The mock-up at LIMA comprised a USV mounting two Naval Strike Missiles (NSM), plus a Protector RWS. The 19m-long USV could also carry UAVs, UUVs or containerised payloads such as a sonar. Able to achieve speeds of 50-60kt, the prototype is to be finished at the start of 2024, at which point the Indonesian Navy will commence sea trials. With a vast archipelago to protect, such NSM-armed USVs give Indonesia the ability to conduct hit-and-run missions against intruders.

Singapore has also developed indigenous USVs. ST Engineering offers the Swift USV 18 and Long Endurance USV (LEUSV) for defence applications. The former can carry up to 5 tonnes on its stern deck, while the LEUSV concept is a 45m-long craft with 28-day endurance that acts as a mothership for RHIBs, for instance.

This is a scale model of an early version of the Sea Sword USV from LIG Nex1 in South Korea. It is being considered by the ROKN. Credit: Gordon Arthur

ST Engineering also offers the Venus family, with the Republic of Singapore Navy (RSN) utilising the Venus 16 in the MCM role. In a pairing of two Venus 16s, one carries a Thales towed sonar array to detect and classify mines, while the other has an expendable mine detection system for neutralisation. They are commanded via a containerised module embarked either aboard a ship or placed on land.

The 6th Flotilla of the RSN operationalised four Maritime Security (Marsec) USVs in late 2021. These 16.9m-long vessels displace less than 30 tonnes, and a SATCOM system permits beyond-line-of-sight operations. The Marsec USV has a 12.7mm machine gun and laser dazzler mounted on the forecastle, while on the quarterdeck is a modified Genasys LRAD-2000X long-range acoustic device.

Market expectations

Given the proliferation of platform development in the Asia-Pacific, along with the possible use of platforms from the US and Europe, the region looks set to retain its market significance for UMVs for the foreseeable future. With the centre of geopolitical strategy moving ever east, the prospects such technologies appear secure.

“We’re seeing rapid demand growth for the use of USVs to gather all types of data,” said Watters, who stated that, as capabilities expand, teaming operations with both crewed and uncrewed platforms will be performed, as well as the “deeper integration of AI” as the next step in machine technology moving to the fore of defence capability.