Feature

Navigating the new frontier: AI in maritime defence

In an exclusive interview, Mandy Long, CEO of BigBear.AI, discusses the company’s collaboration with L3Harris and the pivotal role AI is poised to play in maritime defence operations. Andrew Salerno-Garthwaite reports.

BigBear.AI CEO Mandy Long discusses AI’s role in maritime defence, the human-in-the-loop model, and navigating future regulations in an exclusive interview. Credit: BigBear.AI

In May this year BigBear.AI entered into a teaming agreement with L3Harris to deliver advanced autonomous surface vessel (ASV) capabilities and artificial intelligence (AI) for current and future maritime defence programmes, followed in June and July with extended contracts with the US Army for the Global Force Information Management (GFIM) system and then the Army Test and Evaluation Command Integrated Management System (AIMMS).

Named CEO of BigBear.AI in October 2022, Mandy Long has extensive experience with the various civil and military applications of AI, with time spent in the use of AI in medical and health diagnostics being “eerily similar” to the discussions being had today around autonomous weapon systems (AWS).

“The question goes back to how can, and should, artificial intelligence be used in the context of decisions that impact human life; or could,” Long said.

Having spent years building technology to support some of the most complex decisions that exist - those associated with cancer diagnosis, and complex disease diagnosis - Long stated that the conclusions reached about the use of AI mandate the inclusion of a human-in-the-loop within both health and defence sectors.

“I don't personally like the idea of fully closed loop decision making in those contexts, I want a human to be involved in that because humans are affected. Though, if we look at historical outcomes, we also know that the pure human component is frankly insufficient as well. We're not perfect.

“We have to get comfortable with finding this marriage point…I don't see a near-term fundamental truth associated with replacing the human cognition side of that story,” Long explained.

The role of AI in assisting Autonomous Surface Vessels

As partners in a teaming agreement with L3Harris, BigBear.AI is developing actionable target packages facilitated by an ASV. The company will advance computer vision, descriptive analytics, and predictive analytics, to identify and classify targets, to do geolocation, and to support route prediction. All this works toward the technology’s key goal: supporting the operator in making the right decisions when they are necessary.

Long distinguished two ranges of activity that are central to the company’s application of AI to maritime operations.

As you think about how you deploy and manoeuvre towards higher risk areas and dealing with anomalies, we contribute to that.

- Mandy Long, CEO BigBear.AI

In the short term, one tranche of research is focussed on identification and classification of maritime objects (debris, water buoys, etc.), coupled with layers of additional context to provide ASVs with the awareness to deal with multiple hazards simultaneously, that might otherwise give conflicting signals. “We're partnering with L3Harris Systems so that they can feed that information in, so that they can make more thoughtful manoeuvring,” said Long.

In the broader term, Long identified capabilities associated with descriptive and predictive analytics for two core capabilities that can aid operations. One is event alerting, providing an ASV with an awareness of qualities that should motivate a course of action.

With the benefit of AI, an ASV could makes inferences about a suspect vessel with reference to a number of different factors.

“Is the vessel speeding? Is there loitering? Is there spoofing happening?” said Long, listing considerations the company is examining. “As you think about how you deploy and manoeuvre towards higher risk areas and dealing with anomalies, we contribute to that.

L3Harris’ Arabian Fox outfitted with BigBear.ai’s AI-based forecasting, situational awareness analytics, and computer vision. Credit: Petty Officer 1st Class Vincent Aguirre

“We take that a step further. So, it's not only about what's happening right now. We do route forecasting and heat map work. We say ‘Okay, we believe in the coming hours this vessel based on its profile, what we know about it and our predictive models, this is where we think it's going to be, so that we can begin to deploy around that.’"

On the back end, Long is also developing risk-stratification work for describing macro level trends, such as an uptick in drug trafficking or human trafficking.

Giving operators explanations, not trust

The use of AI in defence technology has been put under scrutiny recently, not least in an ongoing UK House of Lords inquiry into AI and autonomous weapon systems that began in March this year. Much was made of the comparison between AWS and autonomous cars. Both cases involve systems where people’s lives are at stake, but with the transparency around the accidents for autonomous driving, public outcry in these instances has been more forthright.

Long identifies a separate discrepancy in this analogy: “I think the difference that I would give is that in the context of autonomous driving, you're dealing with right-now, near term, contextual summarisation, as mostly the sort of pure derivative of where that decision comes from. There's not a broader historical context that needs to be applied oftentimes to those decisions beyond the nature of ‘What is the layout of this road? What are the typical traffic patterns?’

I would argue that, just like people, a machine's decision-making process is rarely flawless.

- Mandy Long, CEO BigBear.AI

“I think there's a lot closer pattern to medicine. Because of the amount of disparate, dirty, complex, oftentimes obscured, data that is associated with the fact that we still need to get to a decision that impacts a person.”

Witnesses at the House of Lords inquiry raised concerns that when AI is used in decision making within the context of a human-in-the-loop setting, operators can begin to ascribe a greater level trust to the judgement of the AI than the limits of confidence the system is projecting.

Long is well aware of the concern: “Where things get a little bit dangerous, is when there is an assumption - just the same as with people, by the way - that the computer, the models themselves, have all of the information that they need, and that their decision making is flawless. Because I would argue that, just like people, a machine's decision-making process is rarely flawless.”

The counter-scenario to this is one where experience teaches a human operator not to trust the judgements of the AI, potentially at great cost. According to Long, the key to finding a perpetual balance in the relationship between machine and human is to ensure that “explainability never goes away”.

Robot makes wrong decision trying to match geometric primitives in shape sorter game. CreditL Digital illustration via Shutterstock.

For BigBear.Ai, this means underlining the margin of error and the systems level of competence in as transparent a manner as possible. “But it’s not just about statistical confidence…it’s also the derivative of how those models were changed. And that's where you get into some kind of the ethical implications of AI and the bias that can come out of that.

“The way that we get to the place we have a high degree of awareness around what these models are seeing, and therefore, where their recommendations could be coming from, is if the substrate that they run on gets a heck of a lot better,” said Long, identifying the quality of the training data used to build an AI as critical to expanding the explainability of the systems decisions.

Historically, models were often trained, built, and deployed in highly controlled environments, where I had a very large degree of control over the training data. “The level of rigour that I could apply to the training of those models, in the early days of that, was extremely high. I was very comfortable with what was going into the training sets, because I knew exactly what it was.

“I think we're beginning to kind of chip away at now. And a lot of that, frankly, is the result of the what's happening in the world, the level of geopolitical unrest. What we could potentially be facing in the next two to five years, is out of necessity, changing the way that we're thinking about training.”

The prospect of AI innovation during an active conflict gives Long some concern. “We're going to be having to make more kind of real time training and performance decisions. I think that the systems themselves need to be getting need to get a lot better at being able to do that on a dynamic and real time basis.”

Regulate AI within the code by starting with open architecture

Going forward, Long recognised the impetus to regulate AI for its use in national security. From the earliest days of the inquiry in the House of Lords, the first inquiry at a parliamentary level on AWS to be held anywhere in the world, peers have sought a definition for AWS specifically so they could be legislated.

Witnesses for international humanitarian law were reluctant to provide one, because, among other reasons, the pace of innovation means that a definition provided today would be inadequate after only a short period of time.

…most of the vendors that exist in the world right now will spend a lot of money trying to make sure that that doesn't come true.

- Mandy Long, CEO BigBear.AI

Long agrees with this sentiment: “There's no historical precedent for the rate and pace of innovation today, and there is a dissonance between that reality and the reality of how we tend to put regulation in place. We do not have to believe that this is the first time that we've tried to regulate advanced technology.”

For Long, the application of technology to AI for the purposes of regulation can only come about through building the systems with open architecture. “That is a fundamental cultural change to how we think about the use and deployment of advanced technologies, because most of the vendors that exist in the world right now will spend a lot of money trying to make sure that that doesn't come true.

“Proprietary systems still dominate the vast majority of the defence community’s deployments. If we want to think about evolutionary regulation and governance, there’s no better way to do it than with technology.

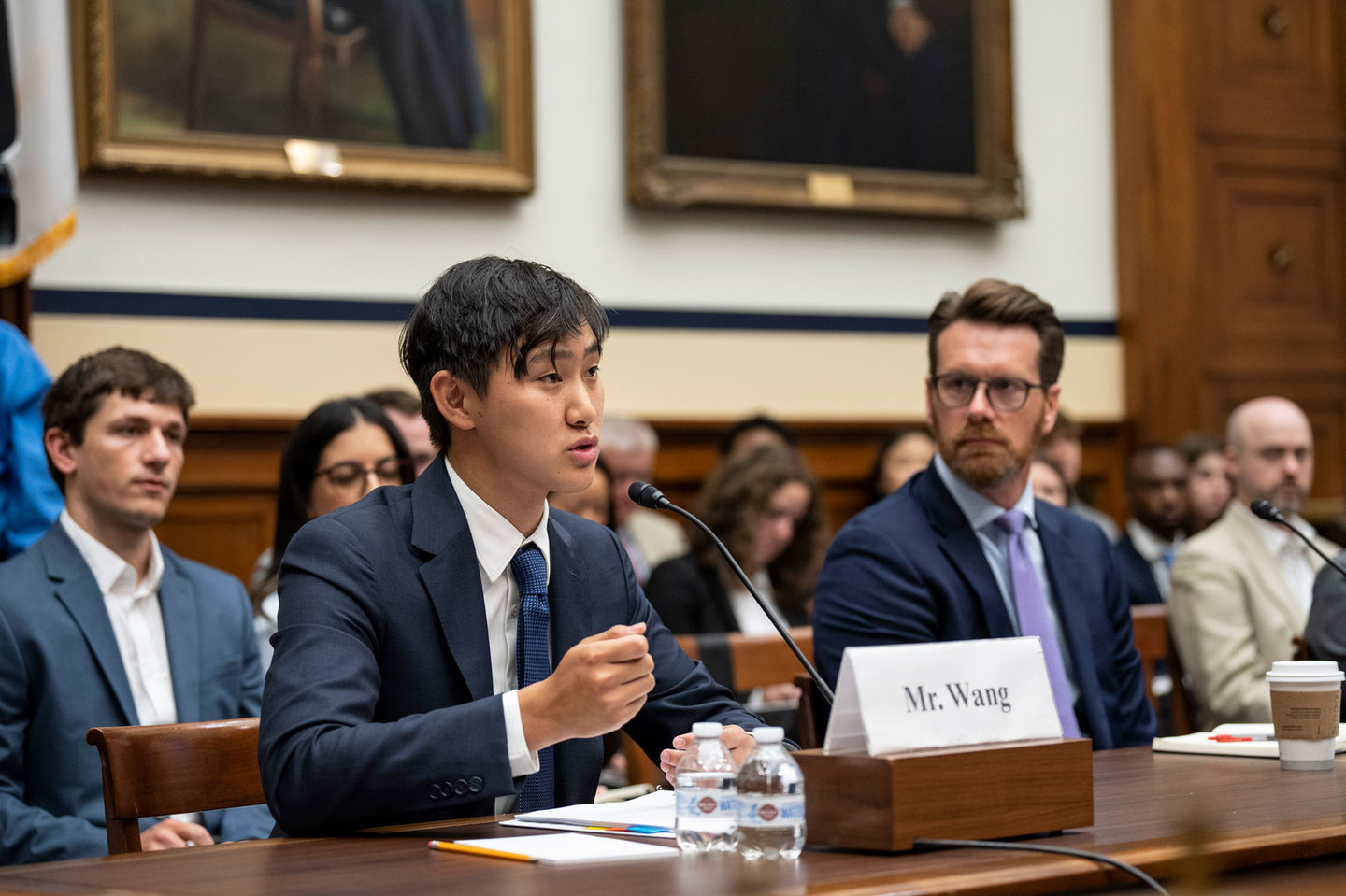

CEO of Scale A.I. Alexandr Wang testifies at a hearing on AI on the battlefield before the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Cyber, Information Technologies and Innovation July 18, 2023. Credit: Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images

“I think the regulatory bodies can play a huge role in helping to force that equation, particularly as they try to make more progress towards these non-competitive behaviours and these proprietary systems that are frankly slowing us down.”

Long stops short of advocating the complete deployment of open-source technology without oversight, or where it hasn’t been tailored to the relevant use-cases. “However, where we're going to find internationally scalable, manageable frameworks and capabilities is in the open source.”