Comment

Is the Russian asset seizure overblown?

Christopher Granville, managing director at GlobalData TS Lombard, examines how political blocks on urgently needed cash for Ukraine is reviving Russian asset seizure talk.

The US Capitol building in Washington, DC. Credit: US Army National Guard/Staff Sgt. Devlin Drew

The drifting oil price sums up markets’ shrug while battles in Gaza and Ukraine rage on: but prospective escalation on a financial front in the Russia vs West struggle deserves attention. This is Western governments seizing the nearly $300bn-worth of Russian assets which they have frozen in their jurisdictions and transferring those funds to Ukraine.

Until now, the moral case for such action has been weighed in public discussions against the legal risks and possible systemic damage to the global US dollar-based financial order. Now, practical necessity may tip the scales in favour of seizure.

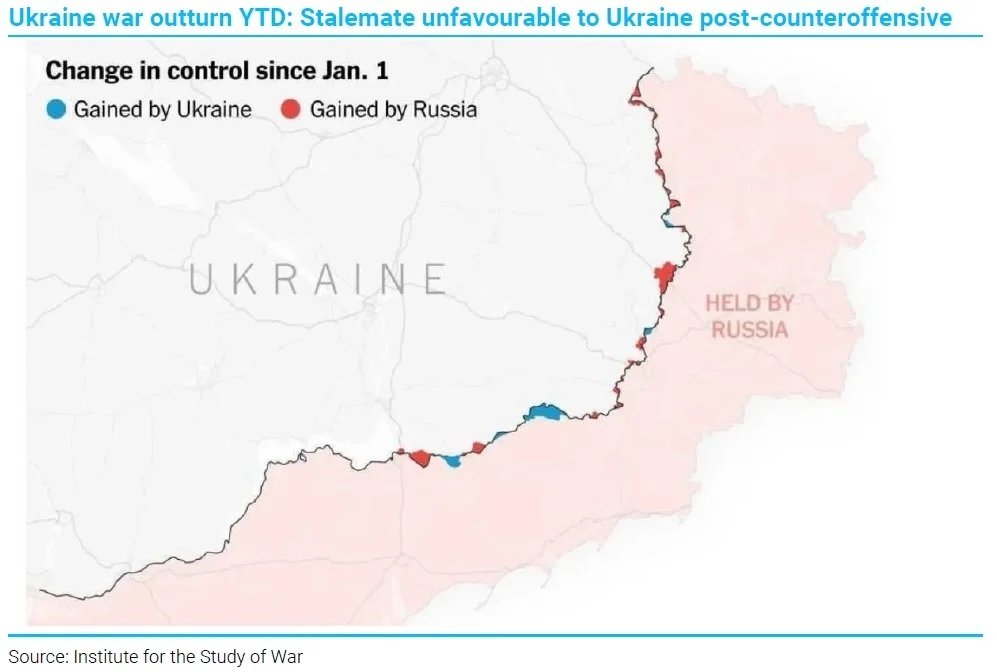

The US and Europe are struggling to provide not only the weapons supplies (especially artillery shells) that Ukraine needs to continue fighting despite the minimal progress of its counter-offensive, but also cash.

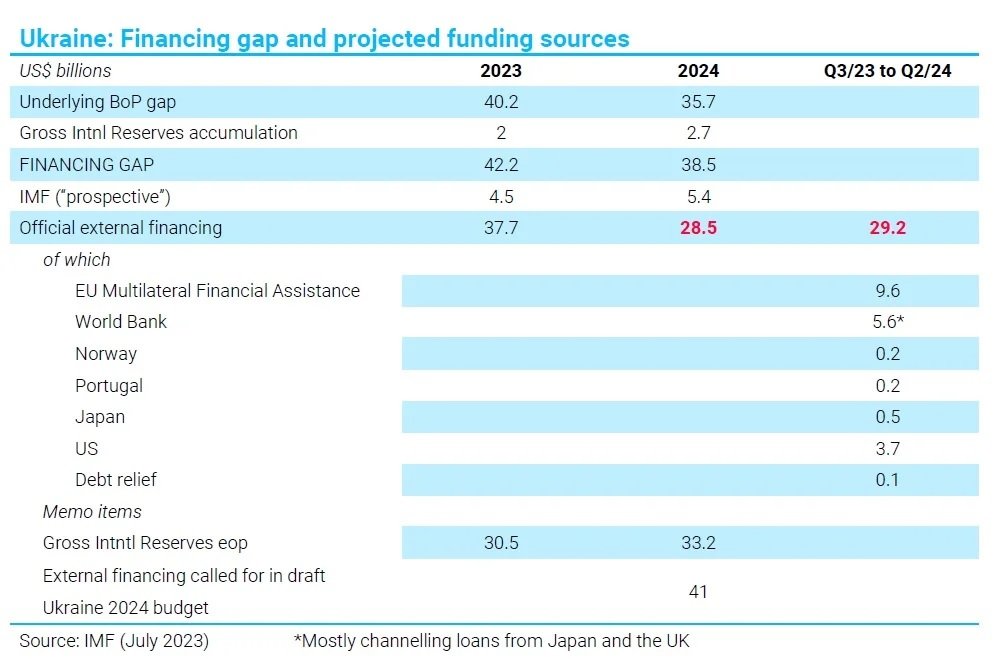

The IMF’s estimates of Ukraine’s financing gap published last July show $28.5bn of official external financing required in 2024 as a whole – and, more piquantly, the same sum from mid-2023 to mid-2024. Presenting the Ukrainian Government’s draft budget in November, Finance Minister Serhii Marchenko warned that the country needs $29bn from Western governments early next year to fill a gaping hole in the public finances.

The noisy US Congressional blockage of the Biden administration’s request for an additional $60bn for Ukraine (most of that earmarked for weaponry) is matched by Hungarian and Slovak objections to the European Commission’s proposal to raise €50bn to cover Ukraine’s financing needs out to 2027.

Although at least a part of the proposed funding will likely be approved on both sides of the Atlantic by year-end, it will be inadequate – forcing Ukraine to drain reserves or fall back on the monetary financing of its budget deficit seen in the 2022, but now contrary to the conditions of the country’s new IMF programme agreed last March and which is itself a source of the needed external financing ($3bn net in 2024). Against this backdrop, it is not surprising to see renewed campaigns to seize Russian assets.

The heavy artillery of legal argument (Making Putin Pay) comes from the Harvard law professor Laurence Tribe. Until now, the Biden administration has limited itself to using the criminal penalty of confiscation in cases of (attempted) sanctions violations. An undisclosed sum belonging to an ultra-nationalist Russian businessman Konstantin Malofeyev was transferred to Ukraine last May, and the US Department of Justice initiated a similar case in September targeting the assets of Oleg Deripaska.

But these oligarch assets account for an estimated $24bn – a fraction of the frozen $270bn of CBR reserves which cannot be ‘got at’ via the criminal law. Tribe’s argument that the US President has the legal power to transfer such funds to Ukraine under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (previously used in this way to seize Iraqi reserves after the 1990 invasion of Kuwait) is of marginal relevance, since most of the frozen Russian reserves are in Europe. Former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers has accordingly advocated coordination with Europe – notably in a letter to the Financial Times co-signed with Tribe and several other luminaries.

For its part, the EU is focused only on seizing the investment income on frozen Russian assets as opposed to outright confiscation. The Tribe paper criticises this approach as taking the same risk to capture only a small fraction of the potential benefit.

The debate about the extent of these risks – above all to the stability of the USD and EUR as international reserve currencies – will drag on in a leisurely way as nothing practical will happen soon. EU foreign ministers approved last month the Commission’s work on possible ways to seize the Russian investment income. These Commission proposals are due by year end. At that point, the EU will be embroiled in gruelling negotiations not only about the supplementary budget (including the proposed €50bn for Ukraine) but also – and much more sensitive for markets – about its new fiscal rule.

Despite widespread political support among European government for using Russian assets to help Ukraine, the required unanimity will be hard to achieve. Reservations and objections will come not only from the ‘usual suspects’ such as Hungary, but also from Germany – where FDP (liberal) ministers in the governing coalition have already flagged concerns about the risk of setting a precedent favouring Poland’s claim for WW2 reparations from Germany. And as signalled by the Kremlin spokesperson recently, any seizure decision would be legally contested by Russia. This points to months-long litigation in the European Court of Justice.

It seems unlikely then that any confiscated Russian reserve funds will reach Ukraine next year. As and when this ever happens, the potential systemic risk comes up against all the usual arguments about the lack of credible alternative global reserve currencies. To this we would add that the belligerents in this economic and financial war will have long since written off all such potential losses.

To take an obvious example: the most symmetrical Russian retaliation for the seizure of the investment income on its frozen reserves would be to confiscate the $1bn of Rosneft dividends received by BP this year. But BP announced days after the Russian invasion in February 2022 that it would be taking a $25bn charge on its 20% shareholding in Rosneft. The practical effect of any seizures of Russian assets by the West would probably be limited to generating incremental momentum to initiatives like the use of CBDCs in the BRICS grouping for trade settlement and finance.

To sum up, is this prospective Russian asset seizure a ‘storm in a teacup’? In its own terms, most likely ‘yes’; but this story is part of a wider and still dangerous prospect of escalation when one or the other side appears to be gaining the upper hand on the battlefield. Although the Ukraine war front is stable (see map above), Ukraine is now, militarily, on the back foot.

Western media coverage was becoming more explicit about this. But any prospect of serious peace talks seems illusory. For all belligerents, the stakes are far too high to cut their losses and discuss compromises.

While fighting on for as long as it can, the ‘struggling’ side can be expected to try new gambits. For the Ukrainians, this may mean something designed to cause (even) more direct US/Nato involvement in the war – which seems the only way now to tip the balance decisively in their favour.

Thus, and as usual with geopolitical analysis, we are left with imponderable but fattening tail risks. The equivalent tail risk in the Israel-Hamas war is the expansion of the conflict to the wider Middle East region including the oil producers. In contrast to the remoteness of tail risks (by definition), the exit route from these wars will most likely be strewn with alarms, which, even if they prove mere feints, will fuel perceptions of fattening. The practical conclusion for now therefore remains that there will be a firm floor under the oil price.

Christopher Granville is managing director for EMEA and Global Political Research at GlobalData TS Lombard, a globally renowned independent economic and investment strategy research provider with a 30-year track record of actionable ideas.

Caption. Credit:

General Sir Chris Deverell, former UK Joint Forces Commander, recently appointed as Goldilock’s Strategic Adviser for Defence. Credit: Goldilock.

The biggest rare earth mines are located in China, and this source of domestic production has helped drive Chinese dominance

Gavin John Lockyer, CEO of Arafura Resources