Sea

War of the waves: the past, present and future of electronic warfare

With a staggering amount of modern equipment dependent on the electromagnetic spectrum, the war for electronic overmatch is constantly being waged in the airwaves. Berenice Healey explores the latest developments in the field.

Electronic warfare (EW) has been a feature of modern conflict since the first battlefield radios were introduced, but it has come a long way from simply jamming radio comms. Electronic warfare systems sense, exploit, and control the electromagnetic spectrum (EMS) to enable armed forces to conduct operations.

Military personnel rely on the EMS for navigation, positioning, communications and other capabilities; EW ensures those capabilities for allies and denies them to adversaries.

At an online event in November hosted by the non-profit Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association (AFCEA), US Army cyber and electronic warfare deputy director Stephen Rehn offered a glimpse of the future of EW.

Currently under development, the Modular Electromagnetic Spectrum Deception Suite (MEDS) would be able to replicate the emissions an army unit of different sizes would produce. This means an adversary would waste time investigating it or avoid the area altogether; it would also create noise to obscure genuine signals.

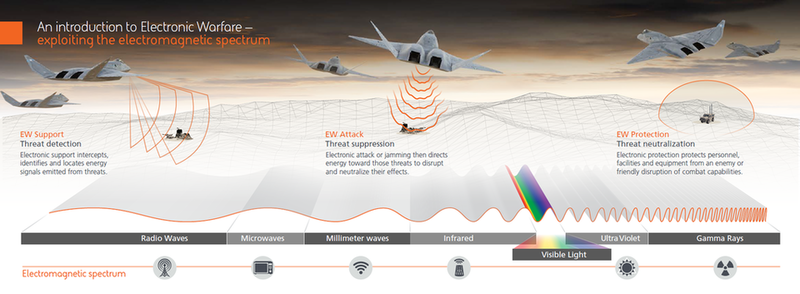

// Infographic from BAE Systems explaining the three main elements of electronic warfare. Credit: BAE Systems

BAE Systems

While it will be some months until the US Army can share more details of its MEDS programme, BAE Systems is one prime that supplies current state-of-the-art EW solutions, including the systems aboard the F-35.

BAE Systems told us via a company spokesperson: “There are three main elements to EW: electronic support, electronic attack, and electronic protection. Electronic support intercepts, identifies and locates signals emitted from threats. Electronic attack directs energy toward threats to disrupt and neutralise their effects. Electronic protection protects people, facilities, and equipment from enemy or friendly disruption or electronic attack.”

Many of BAE Systems’ electronic warfare systems are produced by its electronic combat solutions business area within its US-based electronic systems sector. BAE Systems has more than 60 years of experience in EW; during the Vietnam War era, a BAE Systems legacy company designed the Hot Brick countermeasure system, which tricked heat-seeking missiles with a false heat signature.

// Video showcasing the work of BAE Systems’ electronic combat solutions business. Credit: BAE Systems.

“The Hot Brick was highly successful and is considered the ‘great-grandfather’ of many countermeasure systems today, but was never used in the field,” says the spokesperson. “In 1975, BAE Systems legacy company Sanders Associates patented the primed oscillator expendable transponder, which was an eject-able decoy that emitted an electronic signature larger than that of the aircraft it was trying to protect, which confused guided missiles.”

Since then, BAE Systems says demand has grown for its EW systems to protect aircraft and conduct operations in highly contested battlespaces. The company’s airborne EW systems are flown on over 120 platforms including 80% of US military fixed-wing aircraft and over 95% of US Army rotary-wing aircraft and it is the sole provider to fifth-generation aircraft including the F-35.

“Our EW systems fly on the F-35, F-22, F-16, F-15, EC-130H, EC-37B, and U-2, as well as many other aircraft, including classified platforms,” says the spokesperson. “Two of our most important systems are the AN/ASQ-239 electronic warfare/countermeasure system for the F-35 and the AN/ALQ-250 Eagle passive active warning survivability system (EPAWSS) for US F-15E and F-15EX aircraft.

“ASQ-239 is the world's most advanced, fully integrated EW and countermeasures system. It provides 360-degree situational awareness and rapid response capabilities, and combines radar warning, targeting support, and self-protection to enable F-35 pilots to engage, counter, jam, or evade threats. EPAWSS – which leverages EW technology from fifth-generation aircraft – also provides advanced aircraft protection and situational awareness, and combines radar warning, targeting support, and self-protection capabilities.”

BAE Systems’ EW research and development is focused on improving warfighters' situational awareness and survivability.

Looking to the future, BAE Systems’ EW research and development is focused on improving warfighters' situational awareness and survivability against known and unknown threats in contested and denied environments.

“Our technology areas of focus include advanced electronics, long-range sensors, artificial intelligence, machine learning, intelligent algorithms, adaptive signal processing, and multispectral, cognitive and distributed EW capabilities,” the spokesperson explains.

While the company is unable to comment on whether it is developing an advanced deception capability like MEDS, it says: “We’re committed to delivering EMS superiority and real-time situational awareness to the warfighter as the environment becomes more complex and threats evolve. We're focused on developing EW capabilities that outpace the threats.”

// MARSS is targeting the defence market with EW solutions based on its private-sector security systems. Credit: MARSS

MARSS steps into the EW arena

Newly entering the defence EW market is MARSS, a systems integrator based out of Monaco with a pedigree in providing security for the yachting industry by combining AI and machine-learning technology with sensors to provide dynamic security.

It is now branching out to offer the defence market smart protection, not just for naval assets but also in the air, for bases and at borders. EW provides one layer of protection the company offers.

MARSS’ newly appointed head of countermeasures Stephen Scott has form in the EW sphere: he previously worked at missile systems specialist MBDA as head of future battlefield capability, where he helped to reposition MBDA’s offerings for an evolving threat landscape.

“We've seen a natural growth of the business away from its maritime heritage protecting infrastructure such as naval ports,” he says. “We’re evolving into defence where you're still protecting infrastructure and individuals but you're doing so against the threat that is substantially more serious than a traditional security threat or a small drone.”

When you're dealing with multiple targets coming in, EW and directed energy weapons give you an unlimited magazine.

Scott says that EW plays a key role in a multi-layered defence solution that matches the effect to the threat.

“There are certain instances where EW jamming is going to be the arrow in our quiver that we want to apply rather than a hard kill factor. We’re using tried and tested EW technology from a US supplier that is operationally deployed because we believe it's the best one on the market today and it allows you to match your effect to your threat.

“Particularly when you're dealing with multiple targets coming in, EW and directed energy weapons give you an unlimited magazine. In terms of traceability, if you're able to jam it then you can essentially capture it, and that gives you that political leverage to say, ‘Look, this is a drone this is where it's come from. We managed to defeat it without that collateral damage’.”

Scott believes that MARSS’s relatively small size may be its differentiator in the market. “I’m well-versed in the way primes work,” he says. “They’re like oil tankers and MARSS is like a speedboat.

“We're in a problem space where the threat is constantly evolving, from a nuisance drone at Gatwick Airport to the suicide drones that we're seeing in the Middle East. MARSS is uniquely positioned to be able to continuously modify and improve our systems to respond to that threat, whereas most defence systems have a ten-year development cycle.”

// Main image: Artist rendering illustrating MARSS’ EW security concept. Credit: MARSS