Poland and neighbors may be shifting centre of gravity in European defence and security

Shared history of conflict with Russia and the fear of its resurgent militarism at their borders has pushed these countries to deliver substantial military aid to Ukraine, according to GlobalData.

Outside of Ukraine itself, the historic significance of Russia’s invasion has been felt most acutely in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), where fellow former Soviet states or members of the Eastern Bloc lie. Traditionally this has been Russia’s European sphere of influence, but the end of the Cold War has seen almost every country in the region save a few Balkan states integrate with the EU and NATO.

Shared history of conflict with Russia and the fear of its resurgent militarism at their borders has pushed these countries to deliver substantial military aid to Ukraine and become the biggest proponents of increasing its scope and scale. Their own defence budgets are increasing too, and if the pledges made by Poland since February 2022 are to be realised, the country will be on track to field the largest force in the EU by the end of 2023 with an array of modern and capable platforms.

At this juncture, it is worth assessing CEE’s prospects as an emerging centre of strategic power and influence in the western alliance. Poland’s Homeland Defence Act passed on March 11, 2022, committed to increasing defence spending to 3% of GDP by the end of 2023 and increasing the number of active personnel to 300,000 – but defence minister Mariusz Blaszczak has stated a longer-term goal may even reach 5% of GDP.

Since then, Poland has negotiated contracts for 250 Abrams tanks, 32 F-35A fighters, and a raft of agreements with South Korean firms worth $10-12bn for equipment including 200 self-propelled howitzers, 48 light attack aircraft, 218 rocket launchers and 180 K2 Black Panther tanks – with speculative options for up to 1,000. These deals also benefit Polish domestic industry by setting up K2 production and research facilities in-country.

The ambition of this military expansion naturally raises big questions as to whether Poland can truly afford it. The global macroeconomic outlook is difficult, and Poland is seeing inflation rates predicted to average at 8.3% during 2023-24. This can place strain on exchange rates and thus technology or equipment import – but Poland likely believes short term difficulty will be outweighed by the benefits of expanding the local defence industry.

Regional defence efforts

Additionally, Poland enjoys significant advantages in Purchasing Power Parity, where labour and salary costs may make its budget highly competitive with the biggest spenders in Europe. Outside of Poland, its neighbors to the north and south have also impressed observers with their resolve against Russia’s invasion and their commitment to military aid. The Czech Republic has invested millions through its major manufacturing conglomerate CSG into repairing Ukrainian vehicles, upgrading and donating Soviet-era main battle tanks, and even employing thousands of Ukrainian workers in its factories to establish new lines of production.

Despite its limited stocks, Slovakia has donated a significant portion of its rocket artillery, howitzer and infantry fighting vehicle fleet. The Baltic States of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia are in a uniquely vulnerable position: despite being NATO members, they are exceptionally small and wedged between Kaliningrad, Belarus and Russia proper, meaning a swift attack could quickly cut them all off from the alliance. Latvia has committed the most aid as percentage of its overall GDP, and all three are using significant proportions of their defence budget to send weaponry to Ukraine.

It is also important to remember future defence policy in the CEE region will of course be shaped by the still undetermined outcome of the war in Ukraine. It may be the case that Russian military power is so diminished, defence spending forecasts can be tempered – but this is only the most hopeful scenario. Should Russia remain a credible threat however, Poland is likely to commit to its defence expansion and this will naturally have an influence on its smaller, like-minded neighbors.

Germany has delivered substantial aid to Ukraine especially in terms of financial assistance but has drawn criticism for hesitancy in supplying heavier equipment such as missile systems, armored vehicles and crucially tanks. Ukraine was only recently confirmed to be receiving western-origin MBTs largely due to German hesitancy to approve donations of Leopard IIs.

This may have informed Poland’s decision to partner with South Korea and may lead to an emerging competitor in the European defence market if domestic production takes off. For those looking to define the longer-term impact of the war in Ukraine on European defence and security landscape, the role that Central and Eastern Europe is playing can reveal a lot.

The global macroeconomic outlook is difficult, and Poland is expected to see inflation rates predicted to average at 8.3% during 2023-24

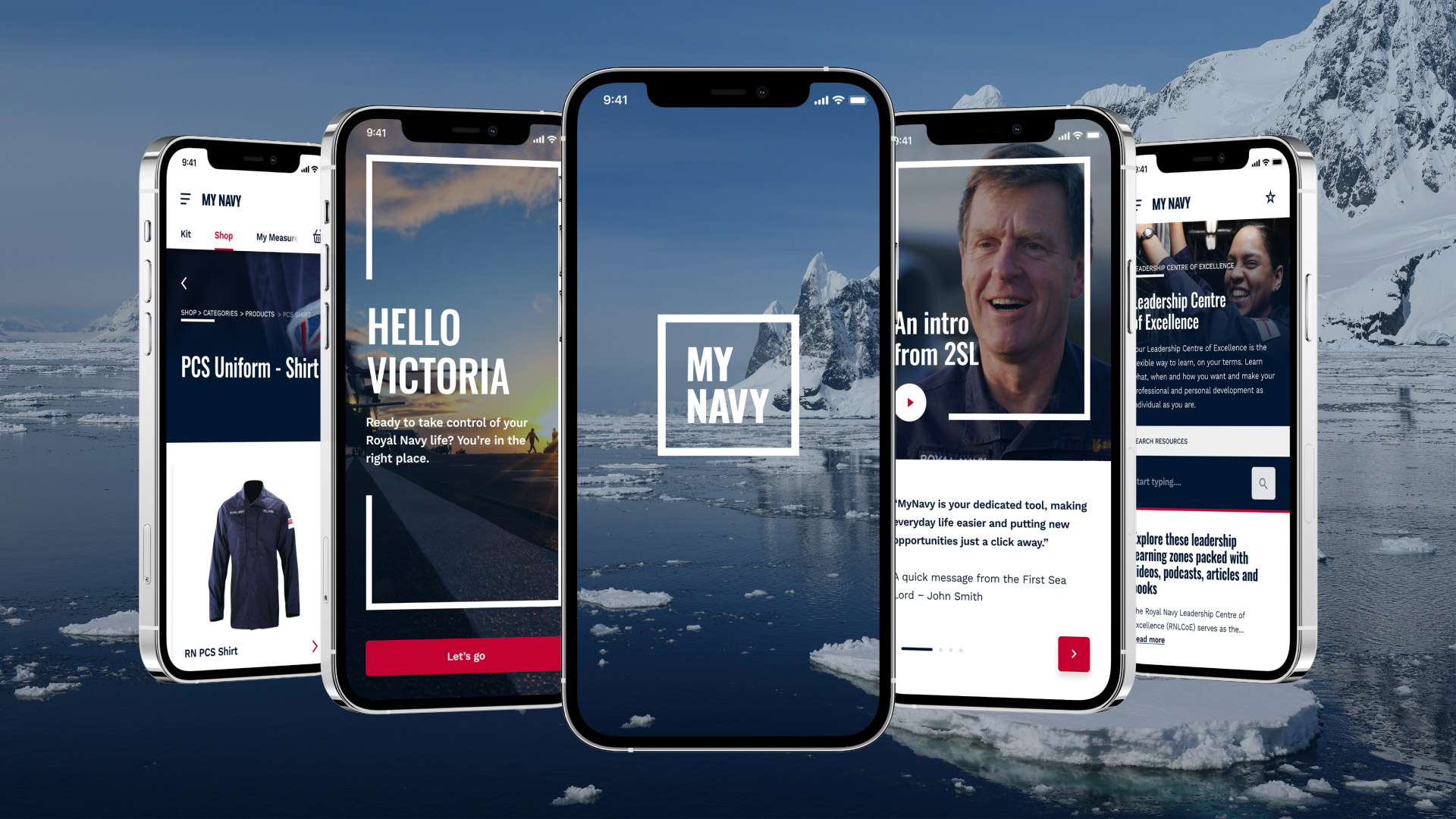

// Royal Navy personnel can use the MyNavy app to request items such as uniforms, providing greater efficiency and speed compared to the earlier analogue process.

// Main image: Poland has invested heavily in its armed forces, particularly in the land domain, and look set to be a regional strategic defence player. Credit: U.S. Army by Sgt Andrew Greenwood

EUROPEAN DEFENCE