UKRAINE WAR

Ukraine-Russia war: a year of conflict

Nearly 12 months on from Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine, the rapid advances and retreats of the two combatants has slowed to a grinding stalemate. Richard Thomas reports.

In the space of 24 hours the UK Ministry of Defence awarded or announced preferred bidder status to nearly £6bn worth of contracts, hours before the Government’s Autumn Statement. Richard Thomas reports.

As we approach the one-year anniversary mark of Russia’s large-scale invasion of neighbouring Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the ebb and flow of the conflict seen in the early stages has slowed to a near-static frontline reminiscent of wars thought consigned to history.

Militaries casualties have been severe on both sides, each desperate (for very different reasons) to gain control of an initiative lost by Moscow’s forces within the first weeks of the outbreak of hostilities. According to Western officials, casualties could run to 100,000 killed and injured on both sides, although the two combatants have sustained different proportions due to differing combat doctrine and in additoin to available frontline medical capabilities.

Civilian casualties are harder to determine, although the indiscriminate direct-fire attacks by Russia on civilian buildings and infrastructure throughout the war will have resulted in significant loss of life. More gruesome acts from Russian forces came to light as Ukrainian forces liberated towns such as Bucha, uncovering signs of mass war crimes.

From the initial Russian efforts to seize Kyiv in lightning airborne and armoured assaults, which failed in the towns and villages outside of the Ukrainian capital, to Moscow’s push through the southern axis past Mariupol and towards Odessa, the ambition of Russian President Vladimir Putin has been the conquest of Ukraine with a view to the formation of a puppet government or client state to act as a buffer to what he considers NATO expansionism.

With Ukraine, led by President Volodymyr Zelensky’s administration, moving politically towards NATO, the likelihood that Russia would accept a status quo with its annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula in 2014, and the ongoing Moscow-backed uprising seen in the country’s eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, was, at best, slim. Russia decided its only course of action was war, and European and world markets have been torn asunder since as its effects are felt far and wide.

NATO moves to support

Faced with the prospect of Russia overthrowing the elected government of a neighbour, NATO moved to act, although this was by no means uniform in its approach as members such as Germany juggled with national interests heavily tied to Russia’s energy sector. Initial support, led by the UK, saw infantry and anti-tank weapons such as the famed NLAW provided, playing no small part in enabling Ukrainian personnel to meet Russian columns and units with a least a technological parity, and in some cases, an advantage.

Over the coming months, NATO countries have pledged huge sums of financial and equipment support to Ukraine, from artillery systems, guided rocket launchers, armoured personnel and infantry carriers, small arms, munitions, infantry training and other crucial battlefield capabilities.

On 21 December last year, President Zelensky, on a rare trip outside of Ukraine, met with US officials in Washington, DC, where it was announced that the US would provide the Patriot air defence missile system to Kyiv to aid in the fight against Russia. Including the what was then the latest round of equipment, the US provided or promised to provide more than 11,000 military platforms for the land, sea, and air domains (crewed and uncrewed) and more than 105 million small arms, mortar, and artillery munitions, among an undisclosed number of other high-end missiles.

Platforms provided included Mi-17 helicopters and T-72 tanks, and western equipment such as the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, 155mm, 122mm, and 105mm artillery, and armoured mobility vehicles such as the M113, M1117, and Mine Resistant Protected Vehicles, also known as MRAPs.

Fighting has stagnated now because of winter conditions, [with] frontline consolidation and heavy losses of equipment on both sides – Tristan Sauer

The increased use of NATO-standard equipment, and the provision of required training by NATO forces in countries such as Germany and the UK, will see Ukraine’s military take on a more European-US bias moving forward. However, Russian-origin designs are likely to remain a prevalent part of Ukraine’s military structure for the foreseeable future, with the defence industrial base already producing air and land equipment from adapted Russian designs.

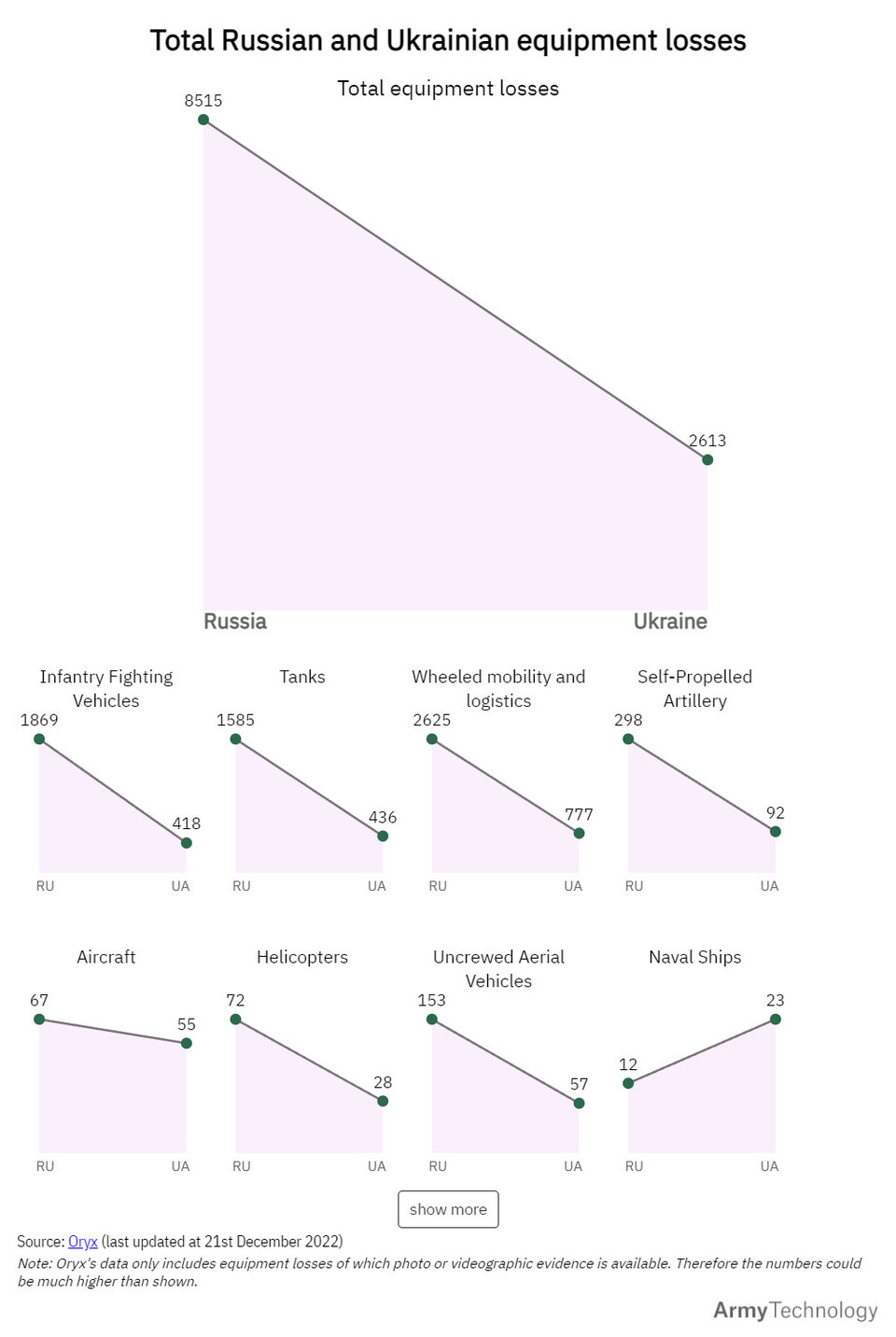

Much of this was provided to replace equipment losses from Ukrainian forces, which in the first 10 months of war combat operations resulting in a level of equipment destruction not seen in Europe since the Second World War, with open-source data indicating a combined loss from the two combatants of more than 11,000 military platforms to the end of 2022.

In terms of equipment lost, the Ukraine-Russia war outstrips losses incurred during the intense urban fighting of Russia’s Chechen wars in the 1990s and 2000s. According to data analysis conducted by GlobalData using open-source intelligence from Oryx, the combined equipment losses of participants in the Chechen wars was 1,059 pieces of equipment, including 412 infantry fighting vehicles.

In addition, more than 200 tanks were destroyed in the fighting, along with a small number of artillery pieces. Airborne assets were also lost by the combatants, including 75 rotary-wing platforms.

In contrast, analysis shows that in the Russo-Ukrainian war between 24 February and 21 December this year, a combined total of 11,128 pieces of military equipment from the two combatants have been destroyed in the fighting. This includes 2,021 tanks and 2,287 platforms that can be described as infantry fighting vehicles.

Artillery, widely regarding as having a decisive effect on the battlefield, has also been subjected to combat attrition, with 390 units lost from both sides, likely through actions such as counter-battery, airstrike, and losses from battlefield retreats/advances.

Combat in the air was hard-fought in the early weeks of the war, although aerial action has dropped off as platforms and pilots have been lost, and anti-access, area denial zones established. A similar number of rotary-wing aircraft have been destroyed in the Ukraine war (100) as seen in the Chechen wars, although losses of fixed-wing aircraft are significantly higher in the skies over Ukraine (122) compared with Russia’s Chechnya combat operations (12).

The latest analysis shows that in the ongoing war in Ukraine, total Russian equipment losses reach 8,515 as of 21 December. In contrast, Ukraine’s military has lost 2,613 pieces of equipment in combat. Human casualties on both sides run into the tens of thousands.

The armoured culmination

As NATO continues to prepare a heavy armour package for Ukraine following Germany’s recent decision to provide its Leopard 2A6 main battle tanks (MBTs) and permit the export of the platform by other operators to Kyiv, questions remain as to what such an escalation means for the combatants in the Ukraine-Russia war and the remaining options open to the Alliance should the tanks not tip the strategic balance on the battlefield.

Berlin caved into pressure from NATO after it had stopped short of promising Leopard 2 tank to Ukraine at the Ukraine Contact Group meeting at Ramstein air base in Germany on 20 January, a move that was met with widespread disappointment from Ukraine and some NATO members. However, in a U-turn on 24 January, Berlin confirmed that it would be sending 14 Leopard 2A6 tanks to Ukraine, a move that also enables other European operators to provide their own packages with potentially up to half a dozen countries thought likely to do so. This could see anywhere from 50-100 Leopard 2 tanks, comprised of the latest A6 model as well as older variants of the Leopard 1 model, sent to Ukraine.

It is understood that Ukraine has claimed that 300 modern MBTs have been pledged by NATO and allied countries, although this claim is difficult to accurate gauge.

“The pressure on Germany to step up lethal aid or at least streamline allied exports has undoubtedly risen due to the mounting urgency of providing critical support before the spring offensives. It was imperative that the Ukrainians could be supplied and trained before the outbreak of fighting, which would complicate planning and logistics,” said Tristan Sauer, land domain analyst at GlobalData, speaking at the time of the German announcement.

On 16 January 2023 the UK was the first western NATO member to commit to sending tanks to Ukraine, although Slovakia had earlier sent 28 M55S tanks over to Kyiv. The move to provide modern MBTs to Ukraine is possibly the final major land platform that could be provided to Kyiv, following NATO members earlier commitments of hundreds of artillery pieces, infantry fighting vehicles, armoured personnel carriers, logistical capabilities, along with hundreds of thousands of rounds of ammunition and advanced munitions, among other military assistance.

// The UK will provide a squadron of 14 Challenger 2 MBTs to Ukraine, with personnel already in the UK training on the platform ahead of the delivery in Kyiv, potentially in time for any spring offensive. Credit: UK MoD/Crown copyright

With both Ukraine and Russia expected to embark on their own offensives in the spring or early summer this year in a bid to break the entrenched front lines in the east of Ukraine, NATO is hoping for a decisive Ukrainian victory that would bring Moscow to the negotiating table. However, a Ukrainian failure could result in consequences for the Alliance and run the risk that the next escalation may result in a general European conflict against Russia.

The prospect of a general conflict between NATO and Russia is still some way off, said Sauer, who considers western caution in overt support of high-level hardware to be dissipating.

“With MBTs, IFVs, missile defence [via the Patriot system] and SAMs being greenlit in recent weeks, two things are becoming clear: Putin’s assertion of ‘full scale war with the West’ is becoming more accurate, and his threats of retaliation now carry much less weight,” stated Sauer.

“The only other major capabilities Ukraine has been asking for have been air assets such as fighter jets and close-air support platforms. The lack of air supremacy by both sides provides a prime opportunity for any force with good air dominance capabilities, however due to the cost and complexity of integrating western air assets into the Ukrainian air force mid-conflict it’s unlikely we will see this happen.”

While some eastern European nations could look to provide Ukraine with Soviet-era air assets, they would not have “transformative” capabilities, according to Sauer, adding that NATO could be required to take further steps if the tanks supplied to Ukraine did not have the desired impact.

“If a non-tokenistic supply of MBTs is not enough to guarantee a Russian military defeat – or force them to the negotiating table in the next year) – the West may eventually concede that Russian belligerence requires more ‘direct intervention’, otherwise western leaders will have to justify huge military expenditures and the donations of materiel for no tangible benefits,” Sauer said.

For its part, the US has confirmed that 31 A1 Abrams tank would be given to Ukraine, along with a training package for Ukrainian personnel. However, in a cautionary note, senior Pentagon officials confirmed that the tanks would not be provided to Ukraine in the near-term, with the plan to procure new-build vehicles for Kyiv to operate. Given this, it could be 2024 before US MBTs are actually provided to Ukraine for use in the field.

How does the Leopard compare against Russian tanks?

According to Sauer, the capabilities of the Leopard 2 could be “broadly compared” to Russia’s T-90 series MBTs, both featuring 120/125mm smoothbore main guns, complex armour, and the ability to integrated modern active protection systems. However, Sauer said that all tanks remained vulnerable to conventional anti-tank guided munitions, as seen in battlefields in Syria and Ukraine.

“The critical difference is mobility, as the Leopard 2 has a larger 1,500HP engine and upgraded transmission, making it far more effective at manoeuvre warfare than the Russian T-90s [950HP] which we’ve seen struggling in the Ukrainian terrain. Spring rains will make the terrain relatively challenging, and fast manoeuvre will be critical to breakout from the currently stagnating frontlines,” Sauer explained.

“The pressure on Germany to step up lethal aid or at least streamline allied exports has undoubtedly risen due to the mounting urgency of providing critical support before the spring offensives. It was imperative that the Ukrainians could be supplied and trained before the outbreak of fighting, which would complicate planning and logistics.”

However, the integration of such advanced vehicles into Ukraine’s force structure and coping with the requisite maintenance, repair, and operations (MRO) demands will be a significant challenge.

“Integrating the Leopard 2 is a serious challenge, as being ‘modern/advanced’ they are complex systems with unique features Ukrainian tank crews are unfamiliar with. Ukrainians are far more familiar with Soviet-era platforms and would require additional familiarisation on the Leopards, otherwise their reflexes in combat will result in fatal mistakes,” Sauer said.

“The other issue is MRO of western platforms, as Ukrainian military engineers and industry are also less familiar with these platforms and will take longer to conduct repairs or ‘jury-rig’ solutions when necessary.”

// Germany acceded to diplomatic pressure to permit the export of the Leopard 2 tank to Ukraine, a type commonly operated by European countries and with an extensive support network.

Despite these challenges, the ubiquitous nature of the Leopard in Europe’s militaries has created a continental MRO support capability, that could be utilised to ensure that Ukrainian platforms are able to be maintained and made ready for frontline operations.

“The problems with MRO integration could be offset if Ukraine and its allies create an MRO network where Leopards are cycled between Ukrainian front and allied EU/NATO nation facilities for repairs outside the warzone,” said Sauer, adding that such a move could lead to a new “escalation” argument.

“So, how many Leopards can Ukraine handle depends on the extent of cross-border support once they’re delivered, as if there’s no MRO they become tokenistic at best and a PR liability at worst; if there is support, Ukraine could gradually learn to operate 50-100 [western MBTs].”

As the saying goes, quantity has a quality all of its own, and, despite the sophistication of the Leopard and Challenger 2 tanks, sheer mass and numbers will matter on the expansive battlefields of eastern Ukraine. According to Sauer, if provided in sufficient numbers, a scale measured in the hundreds, then western MBTs could have a “huge impact” on Ukraine’s offensive operations.

“Fighting has stagnated now because of winter conditions, [with] frontline consolidation and heavy losses of equipment on both sides. Both Russia and Ukraine are having to economise on critical equipment, such as advanced MBTs, jets, helicopters, as they cannot replace them at pace during the war,” Sauer detailed.

“Should Ukraine suddenly have a large supply of armoured vehicles, it could conduct new offensives to assault and hold territory – which MBTs are well suited for – while the Russians still struggle to replace their equipment at pace. There is no question that the force which can field the largest number of combat-capable armoured platforms and replace them reliably will succeed in the coming spring/summer operations.”

A decisive year

Ever keen to utilise the symbolic power of anniversaries and notable dates, Russia could seek to bring forward its 2023 spring push to coincide with 24 February this year, in a bid to take the remaining lands of Donestk and Luhansk and completing the illegal annexation of these regions first announced late-2022. It is thought that mobilisation efforts carried out in the autumn and winter of 2022 have filled some of the gaps creating in Russian lines through a year of fighting, although the corresponding readiness of these newly created or reinforced units is also likely lacking.

All signs therefore point towards a sustained period of war in Ukraine, barring any strategic breakthrough by either side in the coming spring and summer pushes. The result of this, outside of the geopolitical domain, will be further loss of life and destruction of civilian infrastructure in a country only sustaining itself due to Western support.

Would this support weaken, an emboldened Russia would perhaps be able to prosecute the war more on its own terms, leaving a NATO very much reduced in terms of influence and opening up a global power vacuum likely to be filled by Russia itself, and, in turn, China.

// Main image: An abandoned battle tank remains in the snow near Yampil on February 6, 2023, amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Credit: YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP via Getty Images