Feature

Dire states: UK frigate fleet status laid bare

The Royal Navy’s surface fleet could slip into irrelevance, with just seven active frigates as of January 2024. Richard Thomas reports.

Royal Navy Type 23 frigate HMS Monmouth pictured on operations in the Gulf in 2009. The vessel has since been decommissioned. Credit: UK MoD/Crown copyright

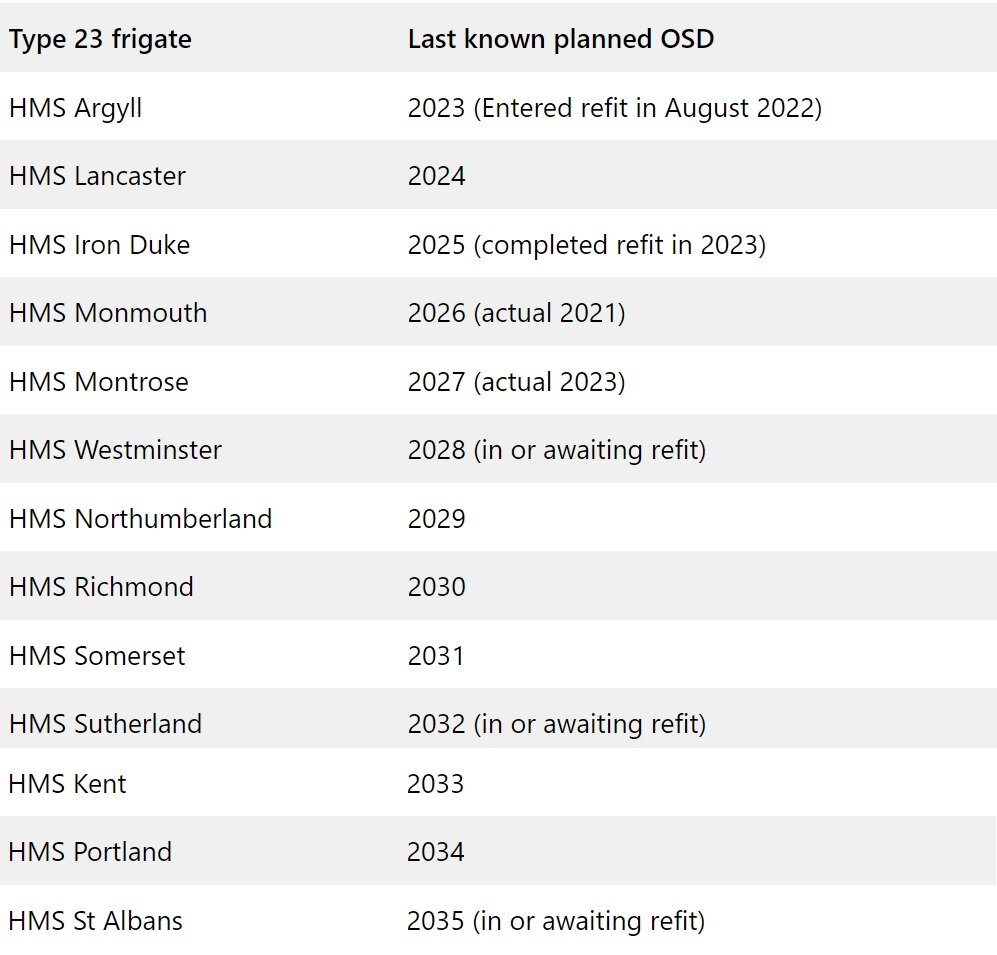

The UK Royal Navy’s frigate fleet could be reduced to a total of just nine hulls by 2027, as a combination of the current timeline for the introduction of the first of the Type 31 and Type 26 surface combatants remains misaligned with outgoing Type 23 vessels.

In a written UK parliamentary written response on 15 January, it was revealed that the UK Royal Navy had 11 Type 23 frigates ‘in service’ – of these, seven platforms were described as being ‘operational’.

The remaining four vessels – HMS Argyll, HMS Westminster, HMS Sutherland, and HMS St Albans – are either currently in or awaiting a refit process, vital to the recertification efforts intended to extend the type’s service life.

During a keynote speech on 15 January, UK Secretary of State for Defence Grant Shapps, responding to media queries about potential cuts to the Royal Navy, said that any frigates removed from service that had served for twice as long as their originally intended service life could not be considered to be “retired early”.

Further, Shapps intimated that there was little point in allowing ageing vessels to undergo maintenance programmes that would only be completed after replacement vessels were already built.

The comments come fresh on the back of concerns over the future of the Royal Navy’s Albion-class landing platform docks, a lead element of the UK’s ability to conduct amphibious assault operations, where UK officials stated that “no decision” had been made on their future.

In an unwanted echo, it appears elements of the surface combatant fleet could be at risk, with vessels such as HMS Westminster thought to be in poor materiel condition. HMS Westminster last saw active service in September 2022 during a SINKEX in the Atlantic with the US Navy, since when has been moored up awaiting its turn in the Type 23 LIFEX programme.

Speaking to Global Defence Technology, a Royal Navy spokesperson said: “The operational requirements of the Royal Navy are kept under constant review. The Ministry of Defence is committed to ensuring the Royal Navy has the capabilities it needs to meet current and future operational requirements.”

Will older Type 23s emerge from recertification?

The oldest remaining Type 23 is HMS Argyll, which spent several years forward deployed in the Gulf region before turning to UK waters in 2020. HMS Argyll undertook gunnery trials in November 2021, before commencing post-life extension (LIFEX) work at Babcock’s Frigate Support Centre (FSC) facility in Devonport in August 2022.

According to Babcock, HMS Argyll is the first Duke-class frigate to receive a post-LIFEX maintenance at FSC for re-certification. According to reports at the time the work would see Babcock perform design changes and integration new mixed crewing facilities, as well as communications upgrades, the overhauling of other major equipment, and a full hull respray.

However, as of 15 January, detailed in a written UK parliamentary response, HMS Argyll is still in the recertification programme, more than 17 months after first entering. The last publicly released out-of-service date (OSD) for the vessel was 2023.

It was previously reported by Global Defence Technology that the overall length of time that a Type 23 frigate is spending in refit and refurbishment programmes is increasing, as the fleet ages and becomes more difficult to maintain. Each ship of the class was originally intended to have an 18-year service life before replacement, but this has been extended through a series of refits.

From 2011-2017 each of the then 13 Type 23 frigates underwent a LIFEX or refit period, with the duration of each programme ranging from 12 months up to 36 months. From 2018 onwards the figures increase, with the first three vessels to undergo earlier work returned to the shipyards for between 37-49 months.

In line with vessel class certification rules, the out-of-service date of warships can be extended for a maximum of six years following completion of each upkeep maintenance programme.

The cost to refit and maintain the ageing class is also a factor, with HMS Iron Duke’s 2023 refit costing more than £100m. By comparison, in the financial year 2023-24, £100m has been allocated for Type 23 refits and of this sum about £50m has been expended, according to official figures.

The case of HMS Argyll, given the above factors, appears troubling given the slippage between its intended OSD of 2023 and its current 17-month long, and still counting, refit.

However, the picture theoretically begins to improve in the late-2020s, with either two or three Type 31 frigates handed over to the Royal Navy in 2027 and 2028, with a single Type 26 commissioned into service from 2028 through to 2035 when the final vessel (HMS London) arrives.

Babcock outlines Type 31 programme progress

Delivering its H1 2023 results report in November last year, Babcock outlined the progress being made on the Type 31 frigate programme, stating at the time the first-in-class HMS Venturer was “progressing through construction” with the ship’s superstructure “taking shape”.

In addition, the main engines, gear boxes, and diesel generators had been installed with supporting systems being fitted around them. The next major milestone of HMS Venturer will be float-off, expected in the first half of 2024.

Manufacture of the second ship in class, HMS Active, has seen the first double bottom block completed in the build cradle, following the keel laying earlier in 2023. The Type 31 build is intended to deliver five general purpose frigates into Royal Navy service to replace five outgoing Type 23 vessels.

According to the UK’s shipbuilding programme, five Type 31 Inspiration-class general-purpose frigates will be introduced into Royal Navy service from 2027, with Babcock apparently tasked to complete the handover of the fifth and final vessel the following year. Following each handover, the Royal Navy will begin a test and trials programme to ensure the vessel is ready for service, with HMS Venturer’s own programme due to be around four years long.

The Type 31 class was born from the realisation by the UK MoD that it could not afford to acquire 13 Type 26 anti-submarine warfare frigates from UK defence prime BAE Systems, instead constraining that programme to eight hulls.

A stop-start competition to determine an alternative five-ship frigate requirement was won by Babcock using its Arrowhead 140 design, heavily derived from the Danish Iver Huitfeldt-class frigates.

However, one potential factor to consider regarding the delivery schedule of the Type 31 frigates revolves around a possible redesign of Ships 2-5, which could have the Mk41 vertical launch system integrated, which could see the currently planned SeaCeptor air defence system (due to be taken from outgoing Type 23 frigates) dropped from HMS Active onwards.

Type 26 – more than a decade from steel cut to commissioning

In April 2023, UK manufacturer BAE Systems began construction of the fourth of an eventual fleet of eight Type 26 anti-submarine warfare frigates for the Royal Navy in a steel cutting ceremony at the company’s Govan shipyard in Glasgow.

The Type 26, which will be known as the City class in UK Royal Navy service, has also found export success in recent years with the design chosen by Canada and Australia to form the backbone of their respective future surface combatant fleets. Australia is building nine vessels to the UK Type 26 design under its Hunter class programme, while Canada will manufacture up to 15 under the Canadian Surface Combatant programme.

The fourth-in-class HMS Birmingham is the first ship to be constructed under a £4.2bn contract for the remaining five ships secured in November 2022, the second batch and effectively completing the order for eight vessels.

However, the difficulties in the build and planned delivery of the first-in-class Type 26 HMS Glasgow for the UK has seen the timeline stretch to the right. With steel cut in 2017 and an expected service entry of 2028, the vessel will have a near 11-year build and commissioning time.

Satellite imagery of the main command centre for Combat Brotherhood 2023. Credit: BlackSky

This is real low-key signalling, to professionals, that they are thinking about this.

William Alberque, director of strategy, technology and arms control, IISS

Caption: The Combined Force Space Component Command Operations Directorate team stands at the first “Rapid Tiger” advanced training event from 28-31 March, 2022. Credit: US Space Force/Lt. Col. Mae-Li Allison

So, these kinds of decisions, which human beings had to do - and human beings, of course, are very intuitive - that intuition also gets embedded with AI machine learning.

Dr Rajeev Gopal, vice president for Advanced Programmes at Hughes.

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.

Total annual production

$345m: Lynas Rare Earth's planned investment into Mount Weld.

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources