Feature

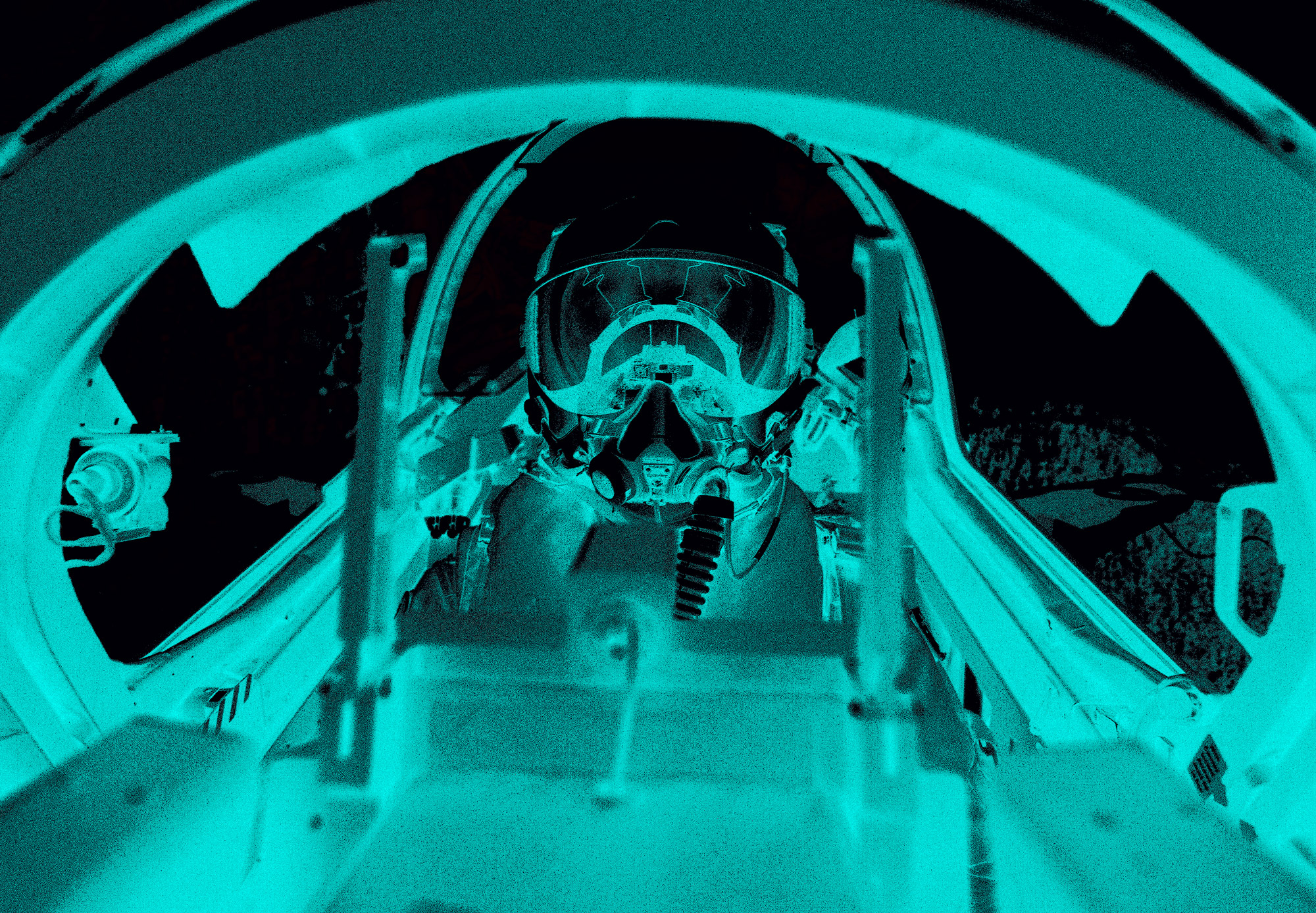

Training ways – where digital meets reality

Militaries are creating new ways to train personnel, bringing financial and operational benefits. Gordon Arthur reports.

Main image: Instructors adjust a scenario for pilot trainees utilising the Air 5428 Pilot Training System. Credit: Lockheed Martin Australia

Cover Story

Eye in the sky

As the first line of threat detection, airborne early warning is a must-have capability for the world’s militaries. Gordon Arthur reports.

Australia was the first country to adopt the E-7A Wedgetail. Credit: Gordon Arthur

New technologies are changing the way that militaries train for war. For example, simulation and live, virtual, constructive (LVC) training bring numerous benefits, since these methods move beyond ‘pretending’, to create realistic, measurable and challenging training environments.

As battlefields grow more complex and unpredictable, legacy curriculums are lagging badly in preparing aviators, sailors and soldiers. Indeed, a ‘one size fits all’ approach does not yield desired results anymore, for personnel must be trained to use critical thinking in dynamic situations.

New technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and online learning are assisting this training revolution towards adaptive learning. This requires an integrated learning environment where data is utilised to personalise each person’s training experience according to their skill level, pace and learning style.

This holistic approach also involves a move towards competency-based learning programmes instead of traditional time-based ones. Such an enterprise-wide view of training – whether in the maritime, air or land domains – improves training management and utilises resources more efficiently.

The DroneGun Mk4 is a handheld countermeasure against uncrewed aerial systems. Credit: DroneShield

Russia has learned how to use its helicopters not just better, but far more effectively.

Lt Col Emiliano Pellegrini, Nato

To modernise the platform, via an April request for information, the USAF is canvassing the inclusion of a new radar, electronic warfare equipment and enhanced

communications to create an “Advanced E-7”. Two such examples are sought within seven years, after which other E-7s could be retrofitted with the modifications.

As for the UK, three 737NG aircraft are currently undergoing modification in Birmingham, the first completing its maiden flight in September 2024.

Global Defence Technology asked Boeing what makes the E-7 stand out, and a spokesperson listing three points. First is its allied interoperability. “With the aircraft in service or on contract with Australia, South Korea, Türkiye, the UK and USA – and selected by Nato – its unmatched interoperability benefits a growing global user community for integration in future allied and coalition operations.”

The US is by far the largest spend on nuclear submarines. Credit: US Navy

Country | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | 2033 | 2034 |

Australia | 3,582 | 3,586 | 3,590 | 3,594 | 3,613 | 3,622 | 6,183 | 6,207 | 6,216 | 6,239 | 6,380 |

China | 2,607 | 2,802 | 3,040 | 3,081 | 3,174 | 3,291 | 3,396 | 3,603 | 3,664 | 3,710 | 4,316 |

India | 2,320 | 2,533 | 3,675 | 2,457 | 2,526 | 2,639 | 2,741 | 2,873 | 2,958 | 3,350 | 3,560 |

Russia | 2,701 | 2,893 | 2,973 | 3,334 | 3,458 | 3,106 | 3,235 | 3,405 | 2,958 | 3,487 | 3,942 |

US | 16,957 | 18,037 | 18,522 | 18,607 | 18,137 | 18,898 | 18,898 | 19,643 | 19,876 | 22,592 | 23,730 |

Lisa Sheridan, an International Field Services and Training Systems programme manager at Boeing Defence Australia, said: “Ordinarily, when a C-17 is away from a main operating base, operators don’t have access to Boeing specialist maintenance crews, grounding the aircraft for days longer than required.

“ATOM can operate in areas of limited or poor network coverage and could significantly reduce aircraft downtime by quickly and easily connecting operators with Boeing experts anywhere in the world, who can safely guide them through complex maintenance tasks.”

Boeing also uses AR devices in-house to cut costs and improve plane construction times, with engineers at Boeing Research & Technology using HoloLens headsets to build aircraft more quickly.

The headsets allow workers to avoid adverse effects like motion sickness during plane construct, enabling a Boeing factory to produce a new aircraft every 16 hours.

Elsewhere, the US Marine Corps is using AR devices to modernise its aircraft maintenance duties, including to spot wear and tear from jets’ combat landings on aircraft carriers. The landings can cause fatigue in aircraft parts over its lifetime, particularly if the part is used beyond the designers’ original design life.

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.

In the air

Simulators reduce operational costs, extend aircraft life, and improve mission readiness, and they are common in pilot training. A simple example of how integrated learning can improve outcomes is a brief study that CAE conducted for the Japan Air

Self-Defense Force two years ago. Around 30 Japanese pilot cadets used VR-based simulators to provide independent instruction and coaching.

Gary Eves, CAE’s principal technology officer, told Global Defence Technology: “We completed the study, and we were able to show that within just one hour of artificial intelligence (AI)-based coaching, I could make about a 20% improvement on their grade performance without an instructor on very low-footprint, independent technology.”

Even more dramatically, CAE claims its technology-based approach reduces the time needed to generate a pilot by 50%.

An Australian pilot trains with a CAE full-motion simulator. Credit: CAE Australia

However, one obstacle is stove-piped pilot training systems and conservative approaches in some air forces. For such situations, it is more realistic to expect them to transform their training system in phases rather than wholesale. Yet when forces procure modern training aircraft, this presents an opportunity to overhaul training curriculums at the same time.

As an example, Saab, Boeing, and BAE Systems announced on 18 November that they had signed a letter of intent to collaborate on a trainer programme leveraging the T-7A Red Hawk as a potential solution for the Royal Air Force’s next-generation pilot training, in a system that integrates live and synthetic training.

CAE and Leonardo offer another model of conducting pilot training. They commercially run the International Flight Training School (IFTS) in Sardinia, Italy, which provides final-stage training for fighter pilots. Around 80 international pilots train there annually.

Marc-Olivier Sabourin, CAE’s division president of Defense & Security, International, said that because of the integrated learning environment that relies on digital training infrastructure, he was “proud to say it’s the most advanced fighter training school in the world as of today.”

CAE supports around 60 defence forces worldwide, training 12,000+ aircrew annually. Furthermore, it has delivered more than 1,000 training devices to date.

Elsewhere, Lockheed Martin’s Distributed Mission Training (DMT) allows F-35 pilots to train together in virtual environments too, connecting geographically dispersed simulators.

Peter Ashworth, Director Global Training Systems, Lockheed Martin Australia, said: “This capability enhances pilot readiness and reduces sustainment costs. By training in a secure, virtual environment, pilots can build skills and confidence while experiencing realistic scenarios.”

Worldwide, the F-35 DMT has trained more than 3,020 F-35 pilots and 18,645 F-35 maintainers to date. Ashworth assessed: “The F-35 full-mission simulator has proven to be a game-changer in pilot training.”

At sea

A key feature of naval training is the challenging pyramid of ensuring mastery in individual skills, through to meshing into sub-teams, teams and then the complete ship operating as a cohesive whole. Beyond that, there is a need for ships to interoperate in task forces, to add air and land elements, and even perhaps combined operations with allied nations.

On a single warship there might be 30 different trades, and all sailors need to remain sharp lest a single person become the weakest link that leads to failure (a sonar operator, for example).

Rear Admiral Simon Ancona (retired), director Global Market Development, Defense & Security at CAE, said there is both challenge and opportunity in the digital training space. He described one problem for navies as being that “they don’t get awarded a fleet in a box. They have legacy systems, so how do you bring what’s available now and in the future, and lay it on a system that’s mostly legacy?”

James Digges, Strategy and Growth - Naval, Defense & Security, Indo-Pacific, CAE, described what an effective maritime training system might look like. He said there must be a digital training backbone that gives a bottom-up approach. This technology backbone can accommodate new modules as well as incorporating legacy systems.

A US Navy sailor virtually cons a ship at sea at the Surface Warfare Officers School in the USA. Credit: USN

Digges said a training system has multiple parts, including connectivity (e.g. a secure cloud) for geographically dislocated elements such as training consoles or an LVC

network. The system’s connectivity links building blocks comprising tangible elements (e.g. bridge simulators or onshore training centres) in dispersed locations, including at sea.

Another element is a performance management system that provides a single but truthful data source. Digges relayed that the Royal Canadian Navy is one service implementing such a holistic system.

Also, as vessels cycle through refit, workup and operations, crews need to be kept “match fit”. Digital training and distance learning allow that, keeping crews sharp whether at sea or on land. Physically exercising a warship consumes large amounts of money and time – as well as impacting the environment and introducing risk – so commanders want ways to keep everybody at optimum performance, and digital training systems can help with that.

Ancona said another danger is that training budgets are often allocated under support elements, and in times of hardship these budgets are often shaved down to protect nuts-and-bolts naval assets. The result of this is that training becomes an afterthought.

On the ground

Brigadier Ben McLennan, commander of the Australian Army’s 3rd Brigade, is overseeing a dramatic overhaul of his formation’s capabilities as new combat systems such as M1A2 SEPv3 Abrams tanks, AS21 Redback infantry fighting vehicles and AS9 Huntsman 155mm self-propelled howitzers arrive in close succession.

McLennan praised training technologies such as tank simulators that assist in the transition. “Practice makes progress, practice makes permanent, and such simulators, amongst a raft of other state-of-the-art simulators available to 3rd Brigade, allows us to practise repetitively, particularly during the height of our hot and humid wet season.

“The Australian Army has invested heavily in the simulation tools that’ll enable our people to realise their high-performing potential.”

Geographically, 3rd Brigade is sited close to the Combat Training Centre at the Townsville Field Training Area, where live instrumentation is available and realistic force-on-force training can occur. On the other hand, a synthetic environment brings many benefits. Instead of moving a complete brigade or division around a training area – which consumes resources – it often makes sense to use LVC to achieve better outcomes.

Urban training complexes with live instrumentation give soldiers a realistic combat experience. Credit: Gordon Arthur

The realism of such synthetic environments continues to increase too, with ‘game-based’ tools such as Bohemia Interactive’s VBS3 software training system.

Incidentally, in the training space there is scope for smaller companies too work alongside established players. For example, Babcock International announced on 26 November that it was partnering with small New Zealand firm Company-X, which specialises in VR training technology. New Zealand’s navy already uses Company-X simulation software, but the tie-up with Babcock should see its technology spread globally.

Future directions

Global Defence Technology asked Mark Horn, Cubic’s director of strategic development, Indo-Pacific, where simulation is heading. He highlighted three trends, the first being the constantly improving realism, sophistication and ease of human engagement of simulation systems (in after-action reviews, for instance).

Secondly, SWaP-C – standing for size, weight, power and cost – is improving. Indeed, enhanced processing power and software are making live simulation systems easier to use and lighter in weight.

The third area of change is artificial intelligence (AI). Although AI has been embedded in target systems that react for many years, robotic target solutions are now able to realistically interact.

The Australian Army inaugurated an Open Plan Weapon Training Simulation System in Darwin in February. Credit: ADF

“AI-based computer vision, range detection and behaviour algorithms enable targets that aren’t smart to detect, classify soldiers and armoured vehicles in training and

accurately shoot back at them. Behaviours can dynamically change to enable the robotic adversary to be more or less proficient, enabling small team training to progress from basic to advanced stages of readiness,” Horn explained.

As for future trends in the military training world, Horn noted there will be more embedded training systems. “There’ll be an increasing trend to embed more and more capable simulation systems within platforms, and for those systems to be able to support training across more of the training curriculum, from individual training through to participation in advanced collective training.”

A second trend that Horn identified is cyber and information assurance. “Simulation systems developed as standalone systems provide a threat vector for cyber actors if they’re not adequately hardened and managed”, he said, adding that cybersecurity becomes more critical when simulation is embedded within fighting systems.

Finally, Horn mentioned the role of data analytics, machine learning, AI and extended reality, which are all making training more relevant and engaging. Simulation is moving from a standalone tool to a core part of building readiness, he pointed out.